Tales of Pacific Pride

|

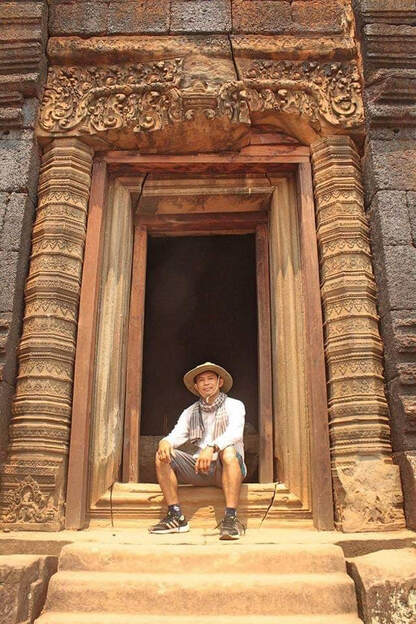

Naga Cambo, Koh Ke Temple, May 2016 | Photo: Melanie Penicka-Smith  We have a guest blogger to introduce to you today. Many of our friends and partners in Cambodia are facing big changes in circumstance due to Covid-19, so we’re welcoming them to our blog to tell you a bit about their lives in the beautiful Kingdom of Wonder. Our first interview is with our friend Naga Cambo. Naga is a tour guide who we first met in 2016. We caught up with him again during our scoping trip in January 2019. He’s an excellent story-teller. In this interview, Naga reveals something of life in Cambodia, particularly under COVID-19, what it takes to become a tour guide, and some of his favourite temples. My name is Naga Cambo and I am an English-speaking tour guide in Cambodia. At the moment I am living in Thnal village, Sro Nge commune, outside of Siem Reap. You know, to act as a tour guide is not so easy. You meet a lot of different people; some want this, some want that. If they seem interested about Cambodian stories, I tell more stories, but if they only love taking photos, I will choose a good spot for them to take photos and I won’t talk much! A tour guide must be flexible. As one proverb says, ‘swallow venom, waste honey’. There were so many subjects that I learned to be a tour guide: first aid, laws and regulations of tourism, understanding the tourist situation, hospitality, tourism statistics and information, the Angkor Apsara Authority, Cambodian geography, participation in protecting and preserving national resources as a tourism guide, Khmer history, archaeology, statues, and Khmer civilisation. Now I would like to bring one of the subjects related to Khmer civilisation to share with you. Khmer people lived in Southeast Asia since pre-historic times, during the stone age. We had our own culture, religion, and performance. We had our own language, but no writing yet, and we lived tribe by tribe. Later on until the first century, the Indian influence gave Khmers two more religions, Hinduism and Buddhism. Hinduism has three main gods at the top: Lord Shiva, Lord Vishnu, Lord Brahman. There are two types of Buddhism, Mahayana and Hinayana [also called Theravada - eds]. We are now one of only five countries that still holds on to Hinayana Buddhism: Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Most of the temples were built for the Hindu cult and some were for the Buddhist cult. We divide Khmer history into three main eras. I: called The Pre- Angkorian Era (1st century - 9th century ); II: called The Angkorian Era (9th century - 15th century ); and III: called The Post - Angkorian Era (15th century until now) and inside these three eras, there are more smaller ones. I tell my clients who never been here before about the Cambodian people: the real living conditions, tradition, culture, civilisation, and any activity that is new or unique that we see on the way and is something that they have never seen in their country. I will not say so much if they’re not interested or don’t ask me more questions. After we know each other and have had a little talk about simple stories, then I say, ‘OK, please let me show you about something in Cambodia’. I start to show them more; especially I focus on my people. There are around 17 million people living in Cambodia. We have more females than male and more young than old. Most of the young people are gone out of the country for a job to places like Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Malaysia and other countries. Some old people still know some French language. I’ll also tell my clients about the marriage age previously and now, the amount of children before and now, about the finances for wedding arrangements, and so on! I have a few favourite temples and they have different features. But I’ll choose one only, so my reply isn’t too long! Banteay Srei temple is one of my favourites, its feature is pink sandstone, when all other temples are grey sandstone. And the carving and decoration are the best compared to all other Khmer temples. Its carving are deep, clear, and so detailed, it looks like a beautiful lady. So that is why it is called Banteay Srei; Srei means ‘lady’. But maybe there are other people whose understanding is not the same as my understanding. You asked me to tell you about the temple I took an Australian archaeologist to many years ago, which was very remote and which archaeologists hadn’t yet been to. That temple is called Phreah Vihea. It is located in the north of Cambodia near the Thai border, in Phreah Vihea province. It was built by four reigns of the king and was Hindu a temple. The first king was named Yasorvaraman I (889-910), the seconnd king was named Rajendravaraman II (944-968), the third king was named Jayavaraman V (968-1000), and the fourth king was named Soriyavaraman I (1002-1050). It is now possible for tourists to go. You asked me what I think about the Stegosaurus Dinosaur carving on Ta Prom temple [the temple where Tomb Raider was filmed - eds.]. There is no clear document recorded, even by explorers or archaeologists. It is still a mystery . But most tour guides describe to their own clients the same way I think. We mostly just understand it may be a Stegosaurus Dinosaur that our ancestors discovered before Europeans, or maybe it is just a monster animal from Khmer mythology. There are not any actual facts to report about this. But it looks so much like a real one! At the beginning of Coronavirus, Cambodians felt very scared. They wore a lot of masks and masks became very expensive everywhere. They worried about their future; no work, no income, everything closed down. And they did not go out, just stayed at home. Most shops and hotels are closed. People became more depressed, including me. I had a serious illness last month, but not Corona! Now Cambodians are seeming stronger, going out more and wearing masks less than before. They have started bicycling a lot to go sightseeing. But everything is still stuck. Right now my day does not look easy. I am too busy with my son and around the kitchen. I have a lot of housework, without income. The temperature is hot. It doesn’t seem like a good life. But I can still tell stories to my son. He always asks me to tell him stories before he falls asleep. - Naga Cambo To book Naga for your next tour to Cambodia, click the CONTACT NAGA button. Pacific Pride Choir’s guest blogs are brought to you with the support of Rambutan Resorts. The folk at Rambutan are LGBTQI+-friendly and socially conscious. Special thanks to Dirk, Tommy and all the staff for their help facilitating these pages.

0 Comments

Sarah sound checking PPC from the audience seats. Photo: Lisa Chanell, Lisa Chanell Photography Photoblog #5 They say a week is a long time in politics. The same is true of touring and rehearsing. Days filled with sight-seeing, rehearsing, enjoying meals together, shopping and relaxing in the pool see days stretch. Time warps. And yet, in some senses before we knew it, it was concert day; the culmination of 2 years of planning. On a Friday night in July, in just 2 hours, it would be all over and we’d be back on the bus, heading back to the hotel for a drink or two and some last minute packing. We had an early start the next day. But all of that was in the future. Here we are in the concert hall of the beautiful Vietnam National Academy of Music, with Sarah sound checking PPC from the audience seats, and PPC and Diversity Choir at their final dress rehearsal. PPC and Diversity Choir at the final dress rehearsal. Photo: Lisa Chanell, Lisa Chanell Photography

Photoblog #4: It’s no mean feat to work with a choir week in week out, building skills and confidence working towards a major concert months down the track. It’s quite another to work with 25 singers, drawn from Australia, New Zealand and the US, having relied on them to learn their parts and to have as little as 12 hours to mould and shape a group before your first Hanoi concert. But this is what PPC does - and did. With 4, maybe 5 singers to a part, from the moment we opened our mouths we felt that we were going to be okay. We had trust; trust in each other and trust in the person out the front leading the group, in this case, Sarah. In this photo we see Susan Haugh, one of the US contingent who was new to PPC. Susan is focussed on Sarah (what a magnificent chorister) and imagining the sound on the tip of her finger. Jonnie Swift is in the background, eagle-eyed and focussed. L to R: Jim Latt (keys), Susan Haugh, Jonnie Swift. Photo: Lisa Chanell, Lisa Chanell Photography

Photojournal #3: When we last met Hà, he was managing a cocktail bar in the French Quarter of Hanoi. Burnt out from activism, he was taking a break and, by the sounds of it, not planning to go back to it any time soon. This trip, we’d emailed to say that PPC was coming, and that we’d love to meet up and introduce Hà to the group. When we didn’t hear back, we were concerned, but wondered if he’d moved on from the bar to a new job outside activism. We were half right; Hà had moved on from the bar and straight back to activism! Taking inspiration from us (how weird is that?), Hà had founded It’s T Time, a transgender community organisation founded by transgender people to create safe spaces for their community. Using art, It’s T Time brings together members of the trans community, their friends and family, creating a safe space for conversation and exploration. Along with his friend, Duong, we met at The Ann to hear Hà’s story, to hear of the work he is doing, and to receive his invitation to any of us to return any time to share our skills with the group in whatever artistic field we practice, to further encourage conversation and understanding. If Hà got inspiration from us, it was nothing compared to the truckloads of wisdom which every PPC member who turned up for that special conversation in the hotel cocktail lounge carried off to bed that night. Members of PPC with Hà and Duong

PPC Photojournal #2: Rehearsals for Pacific Pride Choir 2019 all took place in the small hall at the Vietnam National Academy of Music. The ornately carved wood panelling and plush velveteen chairs created an air of sultry luxury in the summer humidity. This photo tells the story of PPC’s first meeting with Hanoi’s Diversity Choir; DC was less than one year old at this time and its members were drawn from various minority communities, including ethnic minorities, LGBTQI+, people with living with disability, and, to make it truly diverse, some kids and community elders, too. Lisa’s snap of tenors and basses from both choirs mixing shows the instant way our two choir families blended. Photo: Lisa Chanell Photography If you'd been following our blog up to July 2019, you might have noticed something was missing - say, any posts at all about our actual tour to Vietnam and Cambodia? Having blogged enthusiastically on our scoping trips, we'd planned to blog every day once the tour itself got going. ‘It’ll be easy, we know what we're doing now,’ we said to ourselves as months of planning finally came together & the last few things were packed in our suitcase. We had a good schedule; the right balance, we felt, of rehearsals, performances, sightseeing & free time. Surely we could find an hour or so each night, after we ‘clocked off', to gather our thoughts, reflect & blog? In a word, nope. Arriving the weekend before the tour officially started, we planned to spend those few days shaking off the jet-lag, reacquainting ourselves with Hanoi & tidying up a few loose ends. We should have known. So much more happens in direct face-to-face contact than ever occurs over email & by our first Sunday night (a full two days before any official PPC activities were scheduled), a lot had changed already. There’s always more to a tour than just being on time for breakfast & taking the daily roll call as everyone boards the bus. No matter. On Tuesday evening we gathered in the Ballroom of The Ann, our home for the next seven nights, & welcomed PPC 2019. Old friendships were renewed & new friendships began. With 25 singers, equally distributed across the parts, we were a chamber choir & a diverse one at that: LGBTQI+ & our allies. We were grateful for every single singer who embraced this tour & who, by coming with us, committed to diversity, equality & change. Our mere presence is a statement. We might not have been able to blog during our tour, but our dedicated tour photographer, Lisa Chanell, was rarely off duty. So now, while we're confined to barracks thanks to Covid-19 restrictions, we're going to share some of Lisa's beautiful photos with you in a photojournal. The memories might not be in order, but we'll use each one to tell you a tiny story about one of the many special moments on our tour. To begin, here's our first group photo, from the morning of Wednesday 17 July 2019. Ably led by tour guide Ruby, we set off to tour Hanoi: Ho Chi Minh’s Mausolem and former residence, the beautiful yellow house, the One Pillar Pagoda, Temple of Literature, & a rickshaw ride through the Old Quarter. And all before lunch... we were off to a good start. Ho-Chi Minh Mausoleum. Photo: Lisa Chanell, Lisa Chanell Photography

Remember how, on our last trip to Hanoi in May 2018, we met Thư from iSEE? And she said that if we brought our choir to Hanoi, iSEE would found a Diversity Choir to sing with us?

Here they are. Hợp xướng Đa dạng, or Diversity Choir, began less than a year ago, with a call-out to people across minority communities in November 2018, and then casting calls for over 200 people (iSEE had so many applicants they had to stop accepting them). From this, a choir of 70 people has grown into something quite remarkable. Diversity Choir is open to different communities from the elderly to the young, people with disability, LGBTQI+ people, and ethnic minorities. Under the strong guidance of Hoàng Thị Thu Hường, iSEE's Deputy Director, and the passionate teaching of conductor Nguyễn Hải Yến, the choir is sounding great & being applauded across Vietnam. Since forming in November, Diversity Choir has appeared on national television at least four times, being seen on TV and on social media by thousands of people, given concert performances at the Australian and Belgian embassies, and, we think it's safe to say, changed hearts and minds, and even lives, for the better. There's no other choir like it in Vietnam, and as far as we're aware, while there are new queer choruses springing up in other parts of South-east Asia, this is the first Diversity Choir in the region. Like all ground-breaking projects, Diversity Choir has to work hard to demonstrate its worth to its community. iSEE has put a mammoth effort into fundraising to give the choir members the best opportunities possible. Our friends at GALA Choruses have created an opportunity for folk outside Vietnam to show their support for, and value of, Hanoi's Diversity Choir. Can you chip in? It doesn't matter how much. If you know anything about the joy and power of singing, the experience of being a minority, or value the chance to help other people achieve opportunities that inspire them, please join us in showing that we're listening to the new music and powerful message singing its way forth from Hanoi. International supporters, click here. Vietnamese supporters, click here. And thanks. Photos: Diversity Choir's performance at the Belgian Embassy  Mr Sareth's jail at Bakong Mr Sareth's jail at Bakong It’s 11am on Friday 11 January, and Sarah’s in the shower at our Sydney home, watching red dust from a pre-Angkorian temple site swirl around the chequered tiles and wash away. It’s not our usual homecoming; we’re the kind of travellers who prefer a final shower and some calm, tying up any loose ends before getting on the plane. We didn’t expect to visit any temples this trip; we hadn’t even bought a temple pass. So we’re still reeling from the day before, when a last-minute alignment of stars saw us go from our hotel to Angkor to the airport. Our Sydney friend Diana, in Siem Reap to supervise nursing students, had mentioned to us her friend Hun, a monk at Lolei Temple. Hun runs a school alongside the temple, and Diana thought he might be interested in having a choir visit. We were just finishing our packing and preparing for a spot of gift-shopping when Messenger pinged. It was Diana and Hun, with an invitation for us to visit Hun’s school that afternoon. Diana included a photo of the pre-Angkorian ruins she said were part of Hun’s monastery site. We recognised the reddish stone instantly as belonging to the Roluos Group - a collection of three of the oldest temples in the Angkor complex, and among Sarah’s favourites. We have to decide what to do - is it worth paying for a day pass to visit Hun on site for an hour on the way to the airport, or should we just chat more on Messenger? There’s only one way to do things properly though, and that’s in person. If Hun could make time to see us, then we should certainly make time to see him. And so we did. Mr Sareth, our driver, knows exactly where he’s going. We manage to run a little early, so he suggests we stop at all three of the Roluos temples, starting with Preah Ko, and then Bakong. Both Bakong and Lolei have monasteries attached to them. Sarah is particularly excited to see Bakong again - like most pagodas, the walls of the Bakong pagoda are covered in intricate murals depicting the lives of the Buddha or scenes from the Ramayana, but Bakong is especially beautiful. Mr Sareth pulls the car over near the bridge across the surrounding moat. He turns in his seat to face us. ‘Do you see the big white building there, and the one next to it? Khmer Rouge used them as a jail.’ ‘I know, because from 1978-1979, I was in that jail.’ We already know Mr Sareth lived through the Khmer Rouge. There’s a weird calculation that you start to do, usually at some point early on your first trip to Cambodia, where you realise that everyone over a certain age must be a survivor (unless they were out of the country). We’d both run this internal calculation on first sight of Mr Sareth: a small, nuggety man, well-muscled with a deep smile, he looks healthy and strong, but his hair is definitely greying. Although it took a couple of days, he’d already told us he was in jail under the Khmer Rouge by the time we pull up to Bakong, although he didn’t say where. In a flurry of last-minute changes, we’ve inadvertently brought him right to the doorstep of his own deepest trauma. Sarah thanks him for bringing us here, and we ask how he feels being here now. There’s that magnificent smile again; Mr Sareth shakes his head, taps it sadly and, still smiling, says, ‘Very big problems, in here’. The walk across the moat to see Bakong feels desperately sad. We shouldn’t be surprised by what Mr Sareth has told us - the Khmer Rouge turned every public building, including monasteries, into jails. We look at the murals, and sampeah to Buddha, all within view of the place in which Mr Sareth somehow survived, and countless others died, for no reason and in the deepest horror. Lolei was the last of the three late 9th-century Roluos Group temples to be built. Today, its four temple towers are behind scaffolding. There are monastery and school buildings where Mr Sareth parks and also on the higher terrace which holds the temple. Ascending the terrace, we realise it is surrounded by buildings, none of which we paid any attention to last time we visited. Hun is teaching Chinese to a group of school girls. We’ve never met a Cambodian Buddhist monk - at least not on a first-name basis - and we have no idea how to greet this smiling man in saffron robes, a friend of a friend, but also head monk. Before we know it we’re out the front of the class and it’s swapped from being a Chinese lesson to an English lesson. The girls - all either ten or twelve years old, we learn - shower us with questions, with only a little encouragement required from Hun. Their pronunciation is excellent. Mel attempts to draw a map of Australia on the whiteboard. Then one of the girls asks Sarah if she has a husband. ‘No, no husband,’ she replies. Dorothy McRae-McMahon’s oft-remembered words swim to the surface of our minds: coming out is not a one-off experience, it’s a constant choice. Do we choose to do it here, in the shadow of an ancient temple, standing next to a Buddhist monk, in front of a class of primary-school-aged Khmer girls? ‘I live with Mel. We are married - we can do that in Australia.’ The girls regard us steadily; we don’t know whether it’s their English skills that have failed them, or their comprehension of gay marriage. Hun says something to the girls in Khmer, and internally we both brace for, at best, giggles, at worst, grimaces. ‘I told them this is allowed in Australia, but also in Thailand, and also in Cambodia - free choice. Like in Buddhism.’ He breaks into his trademark grin. We look at the girls; they look back at us. They have complete trust in what Hun’s said. One little girl puts her hands over her heart and, fluttering her eyelashes, sighs as if we’ve just stepped out of the denouement of a Disney romance. Hun and his team of volunteers teach around 300 local school children: maths, English, Khmer, sewing, computers and Chinese. Around 25 orphaned boys board at the monastery. The school, called the Friendship Association for Cambodian Child Hope, also helps local kids with school materials such as uniforms, and even scholarships. Hun himself has a Masters in Economics, is articulate, and giant-hearted; his frequent smile borders on cheeky. He explains how he’s been working with Diana’s clinic - his job is to gain the confidence of patients who have been avoiding much-needed treatment in hospital. Many people struggle on with injuries or illness rather than temporarily deprive their families of a breadwinner; Hun has to help them understand the long-term consequences to them and their families if they don’t take time now. Apart from the orphaned kids in his care, Hun has seven cats (all boys too), and we’re not sure how many dogs. We slither down the ancient uneven steps to the prayer hall at the bottom of the temple terrace. Prayer flags flutter in criss-crossing strands across the ceiling and the walls surround us with brightly-painted scenes of the lives of the Buddha. Sarah sings a few notes but we already know we don’t really care about the acoustics. Hun says there are people in the surrounding villages who he thinks will benefit from hearing us. If he can make it happen, then we’ll sing at Lolei. Mr Sareth takes a back-street wiggle to the airport. At the end of the Khmer Rouge, he had the chance to move to America, but chose to wait in the hope of reconnecting with his family. None of them survived. We think of the family trees of Holocaust survivors we’ve seen, the single line surrounded by the blankness of generations rubbed out. The backstreet wiggle takes us past the little restaurant Mr Sareth’s eldest son and his new wife run. In a month, Mr Sareth will be a grandfather. He tells us about his wife, who only needs to shop at the markets once a week now because she can store everything in the fridge. Also we hear about his other children, all of whom are well-educated and in good jobs. Mr Sareth is doing well; there’s enough money for his family and when he has some left, he takes it back to his village and gives it to the poor people there. By way of farewell, Mr Sareth says, ‘I am happy now.’ We knew we were stepping into unfamiliar territory for ourselves, trying to set up a pride choir tour in South-east Asia. What we know from working with choirs is that behind even the most ordinary-looking of people, there’s a complex and compelling story. Making art together creates a space where some of these stories can come to the fore. We had little idea what we were doing or how to go about doing it when we arrived in Vietnam and Cambodia. But we did what we’re good at - hearing people’s stories - and have met people more brave, more generous, more decent, than you could ever imagine. Our stories and our lives are now linked - so will our voices be, come July. Our 2019 scoping trip to Cambodia ends here. Thanks for reading. To join us on the tour this July, follow the button on this page. To donate to Hun's school, click here. ‘Your driver is here,’ says one of the hotel staff as Sarah enters the foyer on Wednesday night. ‘That’s not our driver,' says Sarah, 'that’s our friend.’

Naga Cambo, our tuk-tuk driver from three years ago, has arrived to take us to dinner. We greet each other with a sampeah. There are five levels of sampeah, all involving a bow: for friends - palms together at chest level; for older people or people of rank - palms together at the mouth level; for parents, grandparents or a teacher - palms together at the nose level; for the king or monks - palms together at the eyebrow level; and lastly praying to Buddha or sacred statues - palms together at the forehead. So it’s a nice surprise after the formality when Mr Naga follows up with a hug. It’s good to see him; it’s been two and a half years. May 2016: we arrive for ten days’ holiday in Siem Reap. Our first trip in 2009 gave us a taste for temples off the beaten track; they have few tourists and little, if any, restoration. Whilst you have to see Angkor Wat and the Bayon complex, these lesser-known temples are our favourites. We’ve scoured our Lonely Planet and have made a list. Through the Rambutan, we’ve arranged for a tuk-tuk to collect us and take us to our hotel. Whilst only 6km from the airport, as Deborah said to us recently, 6 kilometres can seem like 20, when your top speed is 38.5km/hr. It’s blisteringly hot and searingly dry; smoke hangs low in the air and the light is an eerie, dirty orange. Forest fires, Mr Naga tells us; people are burning the land to clear it. It’s only mid-morning, but whilst we’re feeling quite refreshed having overnighted in Bangkok, we’ve not really put a plan together. We have a list of about forty temples and a vague idea of half a day of temples, half a day by the salt pool, cooling cocktail in hand. So, even though we’re not that keen to revisit temples we’ve seen, that afternoon Mr Naga takes us back to Ta Prom (made famous by Angelina Jolie in Tombraider). The last time we were here, it was midday, stinking hot, crawling with tourists, and being renovated: the sound of chainsaws was deafening. This time, it’s much more tranquil. We're also on the hunt for the stegosaurus carving. No one knows why or how amongst elephants, turtles, apsaras and deities, there is a single stegosaurus carving (and plenty of people say it’s not a stegosaurus at all - but we reckon it is). From that first stop, ten days of really getting to know the temples, and Mr Naga, begin. We discover Naga also does moto tours when he only has a single patron, and he’s actually taken some quite intrepid travellers to some very remote temples. On the second day, he looks at our list and tells us he’ll take us somewhere more interesting. At first we’re sceptical - we’ve done our research - but after a particularly obscure detour he pulls up at the foot of a towering mound of ancient collapsed brickwork. This is Chau Srei Vibol, and we’re the only visitors. There’s an elderly man who speaks no English roaming the site; he leads us around the leaning pillars and lichen-covered stones held up by strangler figs. This is the kind of experience we’re still a little nervous about, but we get used to it as the trip unfolds. Naga usually lets us know in advance if there’s a self-appointed local guide. Some of these temples are remote, and in a country with limited social security, a dollar from a tourist can make a real difference to someone elderly or disabled whose work options are limited. At Chau Srei Vibol, we quickly became very glad of him, the warnings not to stray off known paths due to landmines in the back of our minds. In the end, we saw 44 temples in 10 days. We climbed 635 steps to reach Phnom Bok, a mountain-top temple with killer views but whose real magic came from the ancient frangipani trees, sprouting gnarled and massive out of the two temple pillars. We trekked up the river bed at Kpal Spean, River of a Thousand Linga (sacred penises), sharing our stash of rambutans with Mr Naga’s friend the policeman who guarded the site. When we told him how much they cost per kilo in Australia, he had hysterics. And we fell utterly in love with Beng Melea, a massive complex which combines the scale of some of the Angkorian temples with the lichen-and-fig wilderness of Ta Prom. We saw more yoni and linga than we could count, stone representations of sacred genitalia, the lips and mouth of the yoni always pointing North, although nothing could top the massive two metre yoni-linga carved out of bedrock on the ring-road out to Koh Ker. It's late afternoon and we're coming to the end of time here; we've just about exhausted our list of temples. As we clamber into the tuk-tuk, Naga turns and asks, 'One more temple? It's on the way back'. Prasat Kravan is a small 10th-century temple consisting of five reddish brick towers. We've driven past it numerous times, both this trip and the last. It wasn't on our list and doesn't look too remarkable from the roadside. At about 5pm, the sky is turning dusky pink; a combination of the sun's weakening rays and smoke from the forest fires which are still burning. The light reflects off Kravan's façade, dramatically enhancing the hues of the red brick. It looks spectacular at sunset. Sensing we're not quite in love yet, Naga advises that we need to go around the back. The temple is dedicated to Vishnu, and the interior of each of the five towers shows large bas-relief images of the god and his consort Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, prosperity and fortune. The carvings are exquisite, some of the best preserved we have seen, as is the Sanskrit which is carved into the posts at the entrance to each tower. Amid the bustle of the Angkor complex, Kravan keeps her quiet secrets, but not from Naga, and no longer from us. He's brought us to his favourite temples, Kravan included, as well as a butterfly farm, to various craftspeople, into the market where he bought his own wedding clothes, as well as countless good places to eat. He's helped us buy forest fruits by the roadside, as well as stuffed frog, and convinced us to try prahok, a fermented fish paste. At this point in his life, Naga hasn't yet become a tour guide - that's still to come - but he's shown us ten days of wonders. If we can help our travellers see even a little bit of the Cambodia he's revealed to us, then everyone will leave this place at least a little bit in love. Naga Cambo: limyiv @ yahoo.com (+855) 92 402 400 A woman, fierce and fluid, is dancing to Tom Waits and a shrieking angle-grinder. She moves through spangled golden light: builders’ dust, caught in the strong Cambodian sun which pours through the open doors at the back of the theatre. We’ve driven through dusty backstreets to find this place, the first black-box theatre in Cambodia, purpose-built for contemporary dance company New Cambodian Artists. The six-year-old, all-female troupe embraces the empowerment of women through expression, but after everything we’ve seen, we’re not prepared for Tom Waits.

‘The girls have been choosing their own music,’ choreographer Bob Ruijzendaal cheerfully explains to us, over the whine of the machinery next door (company manager Khun Sreyneang is finally getting her own office - which she has had painted a good feminist lavender, her favourite colour). ‘We used to do this routine about death to Arvo Pärt, but then one of the girls brought in this song - now we have a whole Tom Waits set!’ And indeed they do - it is by turns haunting, beautiful, darkly funny, and sad. Bob is enthusiastic about the dancers and Sreyneang, and he has a lot to tell us about the company’s attempt to do something new in Cambodia, to challenge traditional roles and forms of expression for women, and to create true professionals with their own marked artistic identities. Bob tell us the women’s individuality and strength is often criticised as arrogant in the Cambodian environment, but he says they’re not arrogant, they just know who they are. We’re fascinated, but the women have clearly heard it all before and only want to get back to their dancing. There’s a seriousness, an edge to this company and these women that’s thrilling to be near. What a pity we’re not here for one of their regular Saturday night shows. It’s been a day of privileged glimpses backstage. Our Wednesday morning began in a familiar environment - the Rambutan Siem Reap, to catch up with General Manager Tommy Bekaert. We’re keen to get his insights into the local LGBT scene. We stayed ten magic days here in 2016, but this time we’re learning about life from Tommy’s point of view. This trip, more than ever, we appreciate that the Rambutan staff have excellent English. Tommy tells us that university training is on offer for all their staff. There’s a common career progression: Khmer with no English start as night-time security so they can study English during the day. After a couple of years, they graduate to the breakfast team and continue their daytime studies. A couple more years and they’re ready to move into any one of the other positions - the welcome team, administration, etc. Rambutan’s newsletter is always announcing the graduation of some staff member or other from university, not just with English, but degrees in hospitality or business. Tertiary education in Cambodia is generally paid for by the student - government scholarships are available, but only for the brightest. No wonder the Rambutan staff are so loyal and the place feels like a family; people are here for the long haul. And they throw a mean Pride pool party as well. We’re reluctant to haul ourselves out of the Rambutan’s comfy couches but our next stop is the Bambu Stage - really a series of stages, purpose-built and flexible for a variety of shows (and meteorologies). Visiting Bambu Stage in the daylight is like going backstage in a theatre; all the ropes and pulleys, usually masked by darkness and leaping firelight, are naked to the eye. Nick Coffill - another Aussie - emerges from one of the many clumps of bamboo shielding parts of the property and apologises disarmingly for his theatre’s daylight garb. He shows us round the ingenious set-up and the various configurations to accommodate everything from live music to shadow puppetry, to fine weather to storms, small crowds or large. We learn about the company structure too; places such as Bambu Stage provide forums both for traditional Khmer art to survive and platforms for new Khmer art to develop, all while paying the artists some kind of wage. Nick is a veteran producer and a half hour’s conversation with him turns up several interesting venues around town, including New Cambodia Artists’ purpose-built theatre. There’s also the Centre for Khmer Studies in Wat Damnak. Nick joins us to visit it, directing our driver Mr Sareth in what sounds like the most fluent Khmer we’ve heard a westerner speak so far. His love for the Wat and appreciation for the instant peace its grounds bestow is evident. We feel the same way, and are grateful for his help as he introduces us to the staff at the Khmer Studies Centre and gains us entry to their conference hall, a modest French colonial building on the grounds of the Wat that would make a choir sound like a million bucks. Nick is the only expat we’ve met who hasn’t spun us a romantic tale of love-at-first-site with Siem Reap, wielding instead a more cynical outlook, but we can tell his respect for the place and its people runs deep. We think of the planning permissions that would be required to construct a new stage or performance space in Sydney, of the years it would take and the money it would cost. Performers like the New Cambodian Artists will spend the bulk of their developmental period in a space purpose-built just for them, by people who seek to plug the many gaps in the artistic market since the Khmer Rouge. And they have stories to tell; the question remains, will the world listen? |

Mel & Sarah

Currently blogging from home, in iso like everyone else, and catching up with PPC19 in the form of a daily photojournal. Archives

June 2020

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed