Tales of Pacific Pride

|

The alarm is set for 8am. No morning meeting means a rare sleep-in. Nevertheless, we're awake before the alarm. No matter; there’s time for a swim and a leisurely breakfast. This morning we’re off to the Vietnamese Women's Museum. It’s been on our radar since friends told us it’s a must-see.

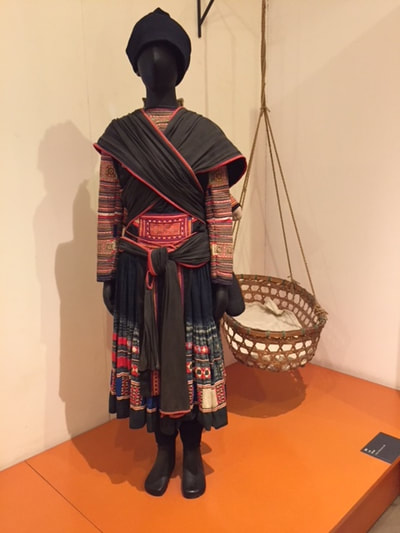

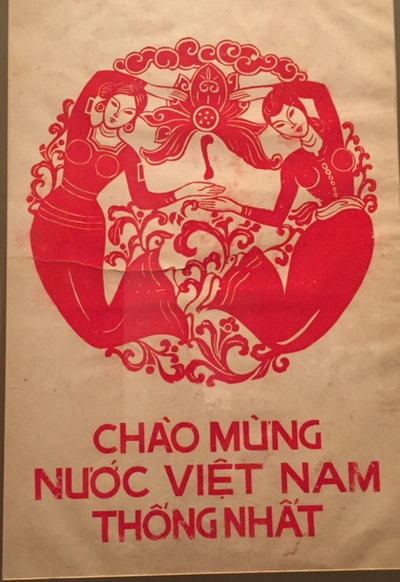

In the foyer, there’s a tall gold statue of a woman surrounded with pink lotus flowers; large portraits of elderly Vietnamese women spread to the left and right, their wizened faces full of a thousand stories. The permanent exhibition focuses on the role Vietnamese women played in the country’s history, and the role they currently play in society and family life. The museum's stated mission is 'to enhance public knowledge and understanding of history and cultural heritage of Vietnamese women ... thus contributing to promoting gender equality.' There are 4 permanent exhibitions: the first, Women in Family, looks at marriage. An information plaque makes it clear that much of Vietnam has always been a patriarchal society. However, some regions were matriarchal, and on marriage it is the man who leaves the family home to join that of his wife. Together we spend much time in the room about the Mother Goddess, discovering that the rituals belonging to her worship involve spirit mediums who channel incarnations of various deities. Like the mediums themselves, deities can be of any gender, creating an interesting space for gender fluidity as the mediums change between them. Mel would have been happy to spend hours in the room devoted to Women in Military. Soft, slightly out-of-focus black-and-white photos of beautiful women adorn the walls. Attached to each is the a story of a young woman, 18, 20 at the most, who served during the resistance wars against a multitude of enemies: a spy working behind enemy lines, a courier, a doctor. These women fought and in some cases died during the Vietnam War. Others spent years in prison, subjected to unspeakable torture. Sarah watches a short film on street vendors. We’ve seen them daily, pushing bicycles with baskets of flowers or fruit; others with a pole balanced on one shoulder, large woven platters on either end piled with smaller fruits and other foods. We’ve not bought anything from them, stopping for meals but not snacks during our trip. 'The next time we come here, I’m buying something from them,' says Sarah. Most of these women are from rural areas who've come to Hanoi seeking work. Perhaps they earn $20US a month to send back to their families. Most are married to farmers, but they don’t earn enough to support a family. Others are the sole bread winner. They work incredibly long hours, sleeping in cheap hostels, and seeing their families only briefly every few weeks or months. We return to the hotel for a quick costume change, before heading out again to our final meeting at the offices of SCDI. The Center for Supporting Community Development Initiatives has a broad remit, working with sex workers, MSM (men who have sex with men), people with HIV, children, and drug users. We’re here because, once again, an Australian friend, Justin Koonin, has introduced us to the organisation. According to its website, SCDI ‘deeply believes that each individual and community has great hidden potential, which can be used not only to tackle their own problems, but also to contribute to the development of the society. Through the approach of empowerment together with policy advocacy, SCDI aims to create motivation and an environment for these potentials to be realized in favor of positive goals.’ SCDI is a little different to the other organisations we’ve visited. It’s the first place we’ve seen clients in the building, sitting on the porch and watching the river that flows opposite. We’re meeting with Ms Nguên Thi Kim Dung, who brings us coffee mugs of cold water and seats us on couches in a new meeting room. We tell her about the meetings we’ve already had, and the ideas that different organisations have suggested for a large-scale, formal, fundraising concert. Kim pauses before responding. These are all organisations she knows, so she understands the issues around the upcoming withdrawal of funding to them. However, she's concerned that a formal concert at the Vietnam National Academy of Music will alienate SCDI's core constituents, who Kim describes to us as low-class. She acknowledges that while music should be for everyone, these MSM and transwomen may well feel that a concert in a high status venue is not for them, something too elite to feel genuinely open to them. We ask Kim for suggestions. A free outdoor concert, perhaps at the Lake. It’s a public space, and for everyone. The Hanoi community is always there walking, or playing badminton, and on the weekend there’s the Night Market. The European community has spent the last month showcasing their various cultures at free outdoor events. The embassies hired the space, brought in a stage. Mel thinks that perhaps one of the embassies can partner with us. Once again we are grateful that we came to Hanoi. We want to include as many parts of Hanoi’s LGBTQI+ community as possible, and while all these NGOs work broadly across queer issues, their specific demographics and areas of focus differ significantly. Internally, we tally up the mistakes we could have made, the people we could have inadvertently excluded, if we’d just landed with the choir and done one show. We thank Kim for seeing us. Before we leave, Sarah ducks into the bathroom. It’s the first place either of us has seen a sharps bin in Hanoi, a reminder both of who SCDI is supporting, and its commitment to providing proper care for people with issues largely invisible to us tourists in Hanoi. Kim’s right - music should be for everyone. We add to our list of tasks how we can help people who feel excluded from much of society believe that Pacific Pride Choir is singing for them too.

0 Comments

Mr Ha, Sarah & Mel, Tadioto Mr Ha, Sarah & Mel, Tadioto People think we’re odd to want to walk in Hanoi. It’s hot, the footpaths are uneven and crowded - either with moto, foot stools, or street vendors - so a distance it would take ten minutes to cover on foot in Sydney takes twice that long in Hanoi. But on our final night, we decide to take shanks’ pony one last time. We’ve been in the American Club (I’ll admit, we were drinking), officially on a reconnaissance trip to see the space, as it’s hosted Pride events in Hanoi before. The club is owned by the US Embassy, and foreign embassies provide both moral and financial support to many NGOs working on civil rights for LGBTQI+ people. (The Australian embassy’s held a Mardi Gras event before - go, Aussie, go! - and the American Club is going to host a queer prom night in the near future.) By the time Chris joins us for a drink, Mel and I can attest to the suitability of the space, both the sprawling outdoor setting, which would make a great after-party venue, and the generous beverage servings. It’s the first time anyone in Hanoi has popped over to our table to check how dry Sarah likes her martinis, and where she feels game enough to ask for it to be ‘a little bit dirty’. Under Chris’s guidance, we roll down the street to try roast chicken from a street vendor, and skirt the lake, busy as always with locals and tourists taking the air. All work and no play make Sarah and Mel very dull, so after we hug Chris goodbye, it’s off for a spot of shopping. As always Mel is on the look-out for t-shirts. With Tintin safely stowed, we start the walk home. It’s a nice night, and it gives us time to reflect on the last week, the people we’ve met, and the ideas we have for 2019. We’re starting to recognise streets. ‘Aren’t we near Tadioto?’ says Sarah. A quick check of Google Maps confirms her suspicions - how fortuitous that we walked! There would be no better way to say ‘bonne nuit’ to Hanoi than a last drink at Tadioto. Maybe Ha is working again tonight; he is the manager, after all. Once again we enter through the velvet drapes. This time, Ha welcomes us like old friends, a beaming smile on his face. We’re shown to the same table as before, and he’s even remembered our drinks order (the bar makes a really good martini). But when we order white wine, three glasses turn up at the table. Ha will join us. He offers his story. It’s complex, yet familiar. We’re keen to understand the trans experience here, and Ha is one of the foremost trans activists in Vietnam. He is eloquent and articulate in English, probably fearsomely so in Vietnamese. In response to our many questions, his story unfolds, along with various lessons on politics and LGBTQI+ experiences in Vietnam. Ha’s first coming-out was as a lesbian. He worked as a lesbian activist until he found a language and a way of expressing his true identity. Sarah asks if there are words in Vietnamese for these identities (lesbian, trans, etc); if they must all be borrowed from English; or if new words are being made. The Viet words are all derogatory, Ha explains. But identity is a tricky thing, especially for someone like Ha, who is non-binary trans, and feels trapped in a binary worldview, no matter the language in which he operates. Ha went on to work for iSEE as a transman, was involved in forums and support groups, told his own story repeatedly, and nursed many other people through the telling of theirs. Trauma compounded trauma; being strong for people who had no other role-model became debilitating. Eventually there was one phone call too many asking Ha to be the sole public representative of a very private tribe. Too often, if Ha turned down a chance to speak, no one else was prepared to step into the gap. This resonates with Sarah, who spent a year in Q&A; not the ABC TV show, but a youth leadership course for LGBTQI+ people, led by Sydney Leadership alumni Meredith Turnbull, Michael West, and David Hardie. Part of the course’s adaptive leadership model taught that sometimes, for others in a group to learn their own strengths, their leader must fail them. If a leader is always present to do all the work, take all the criticism, find all the answers, the strengths of the community remain hidden, as it relies solely on the individual, no doubt flawed, strengths of the leader. After 10 years of activism, Ha is taking a rest, in the hope others may step into the breach. He’s managing Tadioto, contemplating his next move, hoping to maintain his personal activism. Based on the time he’s spent with us tonight, we would say his personal activism has the potential to be as powerful as his more overt public work. We ask him what we can do, as two white Aussie white queer female musicians, to make some kind of useful difference. Ha is crystal clear on what we should talk about: Vietnamese trans people are stuck in the dual boxes of masculinity or femininity. Somehow, Vietnam needs to open a space for non-binary-trans. Ruefully, we tell him the same thing still needs to happen in Australia. For trans & cis-gendered people both, there is a kind of rigidity inherent in performing gender, which risks forcing people to focus on the presentation of this one aspect of a whole self. As non-binary-trans, Ha is a minority in his broader Vietnamese community, within the LGBTQI+ community, and even within the microcosm of his trans community. It’s the same problem we face everywhere, among all minorities and marginalised groups: to reach a point where definitions don’t matter, we somehow must create a space for those definitions to develop in safety and equality. It’s no small problem that we’ve been invited to consider. We don’t know how far a choir can go towards contributing to the answer, but there's no way we want to let Ha down. Courage deserves courage in return. And while neither of us are particularly brave, we're always game for a challenge. It’s 9am (again), and we’re in a Grab (Uber, Southeast Asia-style), heading to CSAGA. Their offices are only 6km from where we’re staying, but in the Hanoi traffic it's about a 50-minute drive. It dawns on us that if this were Sydney, it'd be gridlock. But the traffic flows. How? A dawning realisation ... there are no traffic lights, and everyone is travelling at the same (albeit slow) speed. Is this another lesson for Gladys?

With our newfound Hanoi navigation skills, we find the street number: 9A. Chris and Fyfe have taught us always to trust the street number, no matter how unlikely it looks, as all premises must list the street address somewhere on their shopfront. 9A definitely appears to be a coffee shop. 'Level 4,' says Sarah and then Mel spots the logo, cunningly hidden behind a pot plant. So there must be stairs inside. We open the cafe door: tables, chairs, a coffee machine, a staff member. 'CSAGA?' we say tentatively. The woman nods, smiles and opens a door completely camouflaged by wall decals, to reveal a lift foyer. CSAGA (Centre for Studies and Applied Sciences in Gender, Family, Women and Adolescents) focuses on gender-based violence, domestic violence, bullying, human trafficking and gay rights. We are meeting with Ms Mai Buoi, head of the LBGTQ program, and Ms Tran Quyen, a project officer on CSAGA’s Women Loving Women (WLW) project. Their air-conditioned office is welcome; Buoi pours tea while Quyen sets up a PowerPoint presentation. 45 minutes later, we're not only very well-informed, but seriously inspired. CSAGA's work is extensive, but their key tools are art and other creative projects. In fact the women can only spare an hour with us as they're leaving for a work trip in the north to film a gay man and a lesbian woman who chose to marry to fulfil expectations around family obligations. It’s a common story, but one that few are prepared to tell. This couple are two of 20 originally approached to tell their story. The others dropped out, fearing a backlash. CSAGA doesn't work only with cis-gendered women, or with lesbians. The WLW program now covers women of all kinds - cis to trans - in relationships of all kinds - homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, sex work, and so on. They also tackle the thorny issue of domestic violence in lesbian relationships, as well as looking after the interests of children mothered by all kinds of WLW. 'Visibility is a problem', Quyen tells us. 'Also, the media do not understand sexuality or gender so they spread false news, reinforcing prejudices.' This is certainly something which resonates with us and we drift again briefly to the Marriage Equality debate of last year. Buoi has visited Sweden, and saw their pride parade. This inspired CSAGA to support a Pride Festival in Hanoi in 2012. It seems that embassies the world over are very attuned to the LGBTQI+ community, some more so than their own governments. We’re at the end of the presentation. It’s our turn now to present our story and to ask how Pacific Pride Choir can collaborate. We all see a synergy between CSAGA's arts and creative programs and the choir. Eagle-eyed as ever, we both spot a very nice gallery space in the presentation slides. Looks perfect for a choir. The two women talk amongst themselves. We stress that we don’t expect an immediate answer. Sarah and I drink more tea and eat the biscuits which have been offered while they debate. Yes - they think that our project is good, and that we can work together. They like the idea of cooperating through the medium of art and in a public space. They know some high profile artists, maybe some dancers too, who could come together with us in a concert. We'll all be in touch, especially Buoi, who has an Australian government scholarship to study leadership in our country. Downstairs, life in the coffee shop goes on, although our world has changed a little bit, and for the better. Back home we’d disconnected from Facebook. Too negative, too agony-aunt, too awful. We tweet, we email, oddly enough, we talk. We don’t communicate with each other via Messenger. As you may have noticed, we're back on Facebook. It’s one way you connect and do business here. We’re learning. It’s also useful: the map attached to a venue’s Facebook page has saved us from aimlessly wandering the streets more than once. But it can also let you down. Last night we set off for Manzi Art Space. We’d finally got the taxi system sorted and were confident that we weren’t going to get ripped off. We drove through peak hour, freshly showered and looking for a good night out. The taxi swings into a little side street, past a Buddhist temple with bells ringing, and our driver sings out, ‘Manzi, Manzi!’ We step out into the evening air, along with several other young people. 'Sorry,' the young woman at the door says, 'there’s a concert tonight'. ‘Perfect!’, we think. 'Can we buy tickets?' 'Sorry, no, it’s a private concert.' So Facebook is good, but not that good. We’ve got an hour and a half until our dinner engagement at Gón, which is about 3km north of where we are. 'Shall we walk?' asks Sarah. We type our destination into Google Maps: destination not found. We look it up on Facebook: nothing. Chris messaged earlier in the day to say, 'It’s near the Sheraton, if that helps the taxi driver'. What taxi driver? And so begins our unscheduled walking tour of Hanoi. It’s along a main road, but the footpath is wide and the going easy. We pass a taxi layover area; drivers squat playing cards and board games. Further on, the ubiquitous plastic stools are being put out. Roadside food vendors are setting up for the night. The noise from the road is deafening; this is not the place for a quiet, romantic dinner. The sun sets, the footpath vanishes, replaced by long stretches of large, uneven gravel. A makeshift light hangs above a doorway, young and old sit on the front step: you soon realise that you are eye to eye with the locals, looking in on their lives. People live less than a metre from this busy road. Their front yard is the highway. It’s dark now, the neon-lit road stretches before us, sweat pours out of us. Sandwiched between the houses is a high-end tailor and a car hire company, a luxury car on display behind a massive wall of glass. The occasional marble-foyered home with sweeping rosewood staircases glitters in between closed shopfronts where families cook dinner and children do homework amongst the piled stock. The contrast couldn’t be any more stark. And so it continues, the houses of the poor juxtaposed with those of the rich, furniture decor stores, and a very trendy wine bar. The red light of the Sheraton is a beacon against the night. We still have no idea where Gón is but we’re on the water, there’s a breeze, and the view across West Lake is spectacular. Eventually, we find Gón and our friends. We’re north of Hanoi because our friend Chris plays baritone sax in a band at Hanoi Rock City, a live music venue that we need to check out. Chris pulls up on his moto; presumably his wife Fyfe, joining us after a work conference call (she works for an NGO, tirelessly, we think) will jump on the back when we head to Hanoi Rock City. Sarah jokingly asks Chris if all 4 of us can fit... Actually, we could; it’s his own piloting skills Chris doesn’t trust. We Grab instead, the local equivalent of Uber. Hanoi Rock City looks like a Spanish hacienda; there’s swing music, and, more importantly, a bar. Sarah orders a dry Martini. She gets a glass of Dry Vermouth ... this is one more in a long list of lessons we’ve learnt. Upstairs it’s Open Mic night, and slightly stoned expats are singing cover songs, and original compositions about love and travel. It’s downstairs we can imagine our choir, under the lanterns, in amongst the swing music, maybe with the big band. We’re contemplating another drink when Sarah’s email pops up with a change of meeting time: our 3 o’clock Friday is now a 10am Thursday, as CSAGA’s office will have a power outage on Friday. It’s time to head home.  Nguyen Thi Hai Vân, Sarah, Mel & Dang Chau Anh; Viet Nam National Academy of Music Nguyen Thi Hai Vân, Sarah, Mel & Dang Chau Anh; Viet Nam National Academy of Music A healthy body and a healthy mind, or so the saying goes. We’ve got an 8am start today so we’re up at 5.30 and heading out for a morning walk. This fits with our usual routine back home, minus Max, the disabled Jack Russell. He’s safely ensconced at home and, by all reports, not missing us at all. 'Left or right?' Mel says. 'Right,' says Sarah. She’s spotted something of interest in the dawn light; movement in a park a block away. We can hear music; hundreds of locals are doing the Hanoi equivalent of morning boot-camp, minus the barked instructions from a beefed-up instructor. There’s gentle music and slow, graceful exercises for the older generation, a vigorous aerobics work-out for the middle generation, a variety of exercise equipment, badminton, and walkers, going counterclockwise around the park. We join the walkers until we muster up the courage to enter the park for some stretches. Back in the hotel and dressed, we realise we’re in matching outfits. 'Now they'll never tell us apart,' says Sarah. Black shirts, grey pants, black shoes, short hair, and brand new Vietnam Pride pins, given to us last night by Thư. Punctuality is key here. We’re in the lobby five minutes early but our tour manager from Phoenix Voyages, Mr Dung, is already there. We have an air-conditioned car to ferry us through the seething streets to the Viet Nam National Academy of Music. Ms Nguyen Thi Hai Vân, Manager of the International Cooperation Dept, meets us. We thought we’d scrubbed up alright, but Vietnamese women are so stylish they put us to shame. Ms Van’s silk dress, amber beads and platform shoes make us look like grubby pigeons next to a finch. Let’s not mince words - VNAM is spectacular. Slightly faded French-style glory on the outside, the small hall is decorated in traditional Vietnamese style with every façade covered in intricate carvings, a spectacular chandelier, and red velvet seats. But it’s the main hall with which we fall instantly in love. The Sun Symphony Orchestra is warming up for rehearsal so we can hear, from the minute we step inside, that the acoustic is crystal clear. We step into the foyer; grand marble staircases sweep upwards left and right. Outside again, we’re joined by Mrs Dang Chau Anh, Head of Conducting. We introduce ourselves, the project, the contacts we’ve made in Hanoi, and what we're hoping to achieve. While both women are keen to help us, it’s hard to describe our project to them. Although two choirs from the US are visiting this year, there’s no precedent for what we’re trying to do. It takes time before we’re on the same page; we learn we need a Vietnamese organisation to partner with us, and to seek official permissions from the government for our concert. Ms Van suddenly figures us out: we should ask iSEE to be our official host and they can invite VNAM to co-organise the concert. Now we feel our new colleagues understand - we’re here for outreach, as well as to make music. We mention Thư’s suggestion that iSEE would like to support starting a diversity choir, so we ask if there’s a conducting student who may be interested in helping. Ms Anh gives us a big thumbs up. Whilst it seems a cliché, there have been a couple of 'six degrees of separation' moments in the last 24 hours. Mrs Anh studied in Sydney for six months and lived in Newtown in the 90s, on Edgeware Rd. We’re delighted when the women suggest a photo. We stand under a photo of Ho Chi Minh conducting an orchestra, choir and the public in August Revolution Square in the 50's. It’s perfect, embodying everything we’ve been discussing both this morning and during our time here. We hope to return. As she shows us out, Mrs Anh suggests that silk is a cooler clothing choice in this weather. Time for new PPC uniforms, we think. ‘It’s kind-of like getting ready for a first date,’ says Mel. We’re both leaning into the bathroom mirror in our stylish new digs, The Ann Hanoi, rumpling our hair, preparing to meet (& hoping to impress) another person we've only spoken to online - Thư from iSEE.

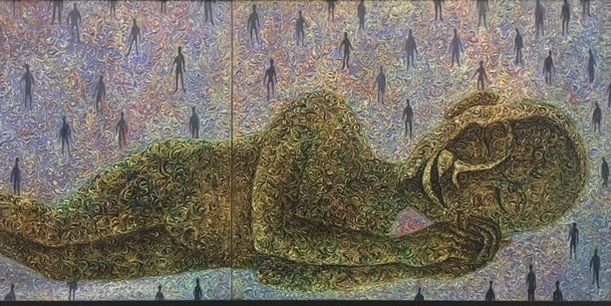

Thư has chosen Tadioto for our meeting, a stylish cocktail bar in Tông Đản, Tràng Tiền. Entering through velvet drapes, we’re met by a friend and former colleague of Thư’s, who recognises us instantly and shows us to Thư’s table. We introduce ourselves, bowing and handing over business cards. Maybe Thư is as nervous as we are, but we’re saved from formulating our first question by the cocktail list. This is a good ice-breaker; Sarah sticks with her usual dry martini (they serve them with olives here, no silly citrus twists) and Mel braves the Long Island Iced Tea. Drinks ordered, we launch in, giving our background: Sarah as the former conductor of Sydney Gay & Lesbian Choir, the choir’s 2014 tour to Riga, and meeting Edyta, the Polish GP with a lesbian daughter. It’s a story that never ceases to inspire, and is woven with anecdotes of raising awareness and media interest in Riga, the work of Kaspars and Mozaika there, and our first Pacific Pride Choir tour in 2017. This resonates with Thư and the work of iSEE, and in particular the diversity advocacy which they do. iSEE describes itself as a science and technology organization. It works towards the rights of minority groups in Vietnamese society through research, policy advocacy, conferences and events, and youth and minority initiatives. It’s a perfect fit for us: according to their website, ‘iSEE envisions a more equal, tolerant and free society in which everyone’s human rights are respected and individuality valued’. We particularly like this part of their mission statement: ‘iSEE celebrates diversity and its promise of a more colourful and vibrant life. Through its works, iSEE promotes plurality and the ending of discrimination against minority groups, especially ethnic minorities, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.’ Thư (Le Phan Anh Thư) is one of two iSEE employees working in the LGBTQI+ program. She tells us there are 14 employees all up, working across LBTQI+ issues, for ethnic minorities, and improving civil society. Part-way through the night, Thư’s friend and colleague Huong joins us. She’s just returned from Myanmar; both women are as surprised as we were to learn of &Proud, Myanmar’s first LGBTQI+ choir. Inevitably, the question of human rights, freedom of expression and freedom of thought arises. Again, these are universal issues. iSEE has had two major successes in the past three years: getting same sex marriage decriminalised (although it’s still not recognised), and providing protections for trans* people under the law. We discuss Australia’s same-sex marriage debate, the role that religious institutions played, and how different groups interpret their rights. We also compare our two countries’ laws for trans* people, which at this point in time, don’t seem to be all that different. A number of iSEE’s programs have been funded through assistance from foreign embassies, particularly the American Embassy. That funding is coming to an end, however, and iSEE now needs to raise funds to further its work. This, Thư says, is where Pacific Pride Choir could be useful: as part of a high profile fundraising concert. Vietnam doesn’t have a culture of philanthropy; according to Thư, that will need to change. Our concert could also be the launchpad of something which really excites us - Vietnam’s first LGBTQI+ choir. iSEE could support this, says Thư. She is keen to hear about our choir and its open-door policy - this is what she wants for Hanoi, a diversity choir which is fully inclusive. Everywhere we go, it seems, Pacific Pride Choir needs to take a different role, and play a different part in the local LGBTQI+ scene. We’re so glad we made this trip. Now the pressure is on for us to make it work. Bringing PPC to Hanoi has the potential to be a catalyst for change in this crazy-beautiful city. No doubt the change would still happen without us. But with us, Thư says there’ll be more momentum, both for a choir and for fundraising. Come on, PPCers, we need you. The evening ends in a cloud of mutual inspiration, admiration, and determination - although part of the admiration is for the fab oil painting depicting famous Vietnamese actor Ngo Thanh Van (Tadioto is full of great art). She’s a babe, and the helpful barman takes a photo of us in front of her portrait. If we could read the name of the artist, we’d tell you. But you’ll just have to visit Tadioto and check it out for yourself. It’s past 10pm (and our bedtime), but we’re in Polygon Musik. It’s smoky, dark, and, to be honest, the kind of place we’d hate in Sydney. But the music’s actually good, the singers in tune, and the mix something you can feel and still keep your eardrums. How does Hanoi do this better than you, Sydney?

We’re here because our new friend Chilli, from Hanoi Queer, suggested we might like to check it out for Pacific Pride Choir. We’ve come straight from two hours’ rehearsal and a very warm welcome from Hanoi Voices, one of only about three choirs here. Polygon is close to the rehearsal venue, and it’s only 9.30pm, so we head out on foot to find the club. This part of Hanoi is slowing down at the end of a very hot day: today the heat index was 45°C. We’re on the edge of downtown; the streets are dim and there are fewer taxis. Women are preparing bundles of vegetables and herbs which will be loaded onto wicker baskets and sold tomorrow. Moto are being wheeled into the ground-floor rooms of houses, and roller shutters are slowly and softly being pulled down for the night. We walk past groups of young men sitting on plastic stools, chatting and smoking. There’s a knack to navigating in this town. Street addresses aren’t always what they seem, and Google Maps is fallible. It pays to open the online map in Facebook and follow that. After a few false steps, we find it, down a driveway and through a carpark. We hear Polygon before we see it. We enter a low-ceilinged room, pay the cover charge and follow the music. It’s smoky in there, and I think it’s safe to say we’re not the target market. It’s been only a short walk, but a far cry, from Hanoi Voices. There, the room is full mostly of expats, auditioned singers, and good - as you’d expect under a conductor as expressive as Dong Quang Vinh (or David to us Aussies). Choirs aren’t really a thing in Vietnam, so there's no queer choir either. The rehearsal at Erato Music School starts at 7pm. We sweat our way up the stairs (everything’s up stairs, here) and introduce ourselves. Then it’s off to help Steve bring some chairs down for rehearsal. David is delighted that Sarah's there as his wife Claire, who is also the pianist for the group, is sick. You know where this is going ... after a quick intro, we’re into warm-up, which consists of breathing exercises & vocalisations. David also invites Sarah to do some vocal warm-ups with the choir, before we launch into Karl Jenkins 'The Armed Man'. It’s moments like these you wish you had Antonio Fernandez in your back pocket! (Mel notes: Sarah did a very creditable job and I’m impressed by my sight singing. Mind you it helps that I’m sitting next to en excellent soprano from Japan.) Next it’s 'Funiculi, Funicula' and sadly, Sarah gets the sack (but oh, so politely). We finish with an arrangement of Beethoven's 'Ode to Joy’. Hanoi Voices are rehearsing for a performance on Friday 11 May in Hanoi Opera House, which is EU Day. Seems that ‘chorister brain’ is universal: performance notes for the week have been emailed, with dates and times. David’s gentle reminders are met with a mix of calm competence, mild confusion, and blank stares. The cat-herding skills of the choral director apply the world over. Before Hanoi Voices (and a detour to Bar Betta, a sexy sprawling club with plenty of space for live music), we began in Hanoi Social Club with two members of Hanoi Queer. How do you get past that awkward stage of talking to someone you’ve never met? We start with experience - what's the experience of being LGBTQI+ in Vietnam? Interestingly for us, Eric tells us they feel safe in public; most issues arise in families and schools. Hanoi Queer isn’t an advocacy group - there are plenty of those already in Hanoi. Instead, Hanoi Queer focuses on creating social opportunities for LGBTQI+ people to meet. Eric tell us that with each generation, it’s easier, too. The younger generation feels more comfortable expressing their identity. The middle generation, not so much: they tend to be more closeted. For 7 years now, there has been a Hanoi Pride week. Not quite your Mardi Gras-style event, rather 1,000-odd LGBTQI+ walking around Hoan Kiem Lake (well, the road is closed already anyway, right?). It’s not officially sanctioned, but then again, like the rest of the population, they’re just walking around the Lake, albeit with rainbow flags. Eric tells us how the police stopped them. We listen, expecting trouble. The marchers replied that they were just walking round the lake, like everyone else. But it was their flags and banners the police didn’t like, and discussion ensued. Then, the march continued, peacefully by the sound of it - just with flags discreetly lowered. Hanoi is a discreet town. People are reserved, and gentle. The warmth is there though, under the surface, along with a definite desire to do right by you. We agree that we can create a concert together, with the main focus being a chance to meet, make friends. We can even learn a song - we’ll find some V-pop (not too many verses, Mel notes), so our audience and new friends can sing with us. The next Hanoi Pride will be a lantern parade, at the time of the autumn lantern festival - there’ll be lanterns anyway, right? So rainbow lanterns will only make things extra pretty. There are ways to do things here. We’re learning them, we think. The steamy streets of Hanoi awake queer echoes of last year’s Pacific Pride Choir tour to Poland and Germany. French-inspired Gothic cathedrals and art deco architecture squeezed in cracks be tween ancient strangler figs, ancient temples with peeling paint, and so many shops, lit with neon, framed with banks of moto.Mel and I are learning what it’s like to be tourists in Hanoi. We missed this step for our first tour, visiting Berlin, Krakow and Poland for the first time along with many of our choristers.

If you’d told me, back in July 2014 (where I stood backstage at a medieval hall in Tallinn, a middle-aged Polish GP hanging onto my arm while her teenage daughter died from embarrassment), that we’d be in Hanoi with that GP's mission not four years later, I don’t know what I would have thought. Tallinn in summer was crowded, and spectacular. We were there with Sydney Gay & Lesbian Choir, on our last stop before the World Choir Games in Riga. Our free concert in Tallinn was packed with both locals and tourists. During the concert, I spotted one woman nodding and applauding everything with emphatic enthusiasm. ‘Lesbian,’ I thought. But she wasn’t. Her name was Edyta, and she was on holidays from Poland with her daughter. They’d chanced to see us advertised that day and came along; because Edyta’s daughter was gay. Edyta found her way backstage to meet me, held my arm with both hands, tugging it for emphasis, as she poured out their story: they were from a border town in Poland; her daughter was a lesbian, fourteen years old; one of the teachers at her Catholic school called her a ‘thing’; Edyta was the only GP in her town who would see queer people in her clinic. ’You have to come to Poland,’ she kept saying, ‘you are needed in Poland. You have to come to Poland.’ I didn’t know what to say. I gave her the choir’s contact details (we never heard from her), and tried to explain that SGLC couldn’t travel all that often but I would tell everyone what she said. That night, in our hotel room, I asked Mel what we were going to do - I met Edyta for all of five minutes but I couldn’t dismiss her request. Like most community choirs, SGLC only travels every five years or so, and it’s a big cost for members, and a monumental effort for the committee. Even if everyone wanted the choir’s next tour to return to Europe, how long would it take us? I can’t remember at what point in the tour Mel and I hatched our crazy scheme - that we’d form a choir built from the members of local LGBTQI+ choirs who wanted to travel more often, and take them to places where LGBTQI+ people struggled to gain recognition.I do know that, on our last night in Riga, we had dinner with Oliver Scofield from KIconcerts, and laid our idea down in front of him. I think we expected him to tell us we were dreaming. He didn’t. And Pacific Pride Choir was born, before we’d left Latvia. It sounds naff, but I have a kind of ‘promise ring’ on my middle right-hand finger, bought in Latvia, which I wore to remind me to keep my commitment to Edyta. And we did. We worked on our proposal, Mel and I and KIconcerts, until it was ready to float with our market: the network of LGTBQI+ choirs in Australia and New Zealand. The first stop was our own choir, Sydney Gay & Lesbian Choir, which I directed and for which Mel volunteered as event manager and stage manager for years. If the SGLC committee said no, we would have let it drop. We’d planned Pacific Pride Choir to supplement the work of our own local LGBTQI+ choirs, not to compete with them. I remember my nerves at the committee meeting in which I laid out the plan: what PPC was; plans for our first tour to Europe in July 2017; our second tour to Southeast Asia in 2019; our intention to tour biennially in the odd years (avoiding the major European and American choral festivals, which many choirs liked to attend); to alternate long distance destinations with closer ones; and our intention to stick to July, a time when we knew SGLC often had a quieter schedule as many people took a break after the first major concert. July was also (and remains) the only time I could manage lengthy travel, for personal reasons. Bless that committee - not only did they fully support the plan as a great opportunity for choir members who wanted to travel more often than SGLC could schedule, some of them said they wanted to come with us. (And one did, and has signed up again for 2019!) I left the committee meeting with the warm fuzzies, and an in principal agreement that our two choirs would avoid travel in the same year as each other. That was the beginning. Any producer will tell you a new project brings heartache, stress, and the constant fear of failure. Also, that that fear of failure isn’t a fear for your professional reputation - it’s the fear one of your dreams will die. Although back in 2014, I wasn’t planning to leave SGLC, I knew I couldn’t stay forever. But the love of using art for social justice that SGLC had given us both was fierce. It would need an outlet. Pacific Pride Choir would be our way of continuing the work that had been one of my greatest passions with SGLC: outreach beyond the LGBTQI+ community. We carried our fear for that dream first time around, when we had 12 people registered for the tour, the deadline passed, and we extended it. We kept breathing and hoping as the second deadline hit, we had 25 people, and KIconcerts said, ‘we’re doing this anyway’. Three months later, at the final deadline, we had 50 people. So, in July 2017, we really did live the dream, as they say. It’s raining now in Hanoi. The people passing on their moto have helmets and multi-coloured ponchos. We’re somewhere between the nightmare and dream - chasing numbers, living in faith (not easy for two atheists). But this time the dream is right in front of us. If I put my hand out past the balcony, I’ll feel it on my skin. Hanoi, here we are, and here we come.  You know when you’ve landed in Southeast Asia (whatever that designation actually means). It’s the air and the smell that you don’t get anywhere else. We love it and it’s what keeps drawing us back to this part of the world. The air is thick, but not in an uncomfortable, Sydney-humid kind of a way. 'It's like stepping through a warm blanket,’ said a friend of ours. He’s right, it’s warm and embracing. Hanoi is a bustling city of xe om (moto), cyclos and all manner of vehicles. The drive from the airport takes you along an amazingly wide road, 4 lanes each way. 'Gladys could learn something here about building roads,’ says Sarah, and we both have a wry chuckle. Further in from the airport, you start to see the Hanoi that I had expected. Roadside stalls with plastic stools drawn up on the footpath, young folk eating bowls of steaming Phó or other street food. Whilst you drive on the right, road rules appear to be flexible with people driving, or rather weaving, to the left if required. The horn is king. It makes crossing the road for the unwary challenging. Oh, and there are few footpaths, so pedestrians mix it on the roads. What also strikes you is the noise: horns, construction, the constant chatter and music. (Sarah says: ‘It’s better than Times Square!’) A night market springs up around Hoan Kiem Lake on Friday and Saturday nights. PA systems play swing and couples dance effortlessly beside the lake. Further around, six 20-somethings dressed in white practice their latest dance routine while the crowd wanders by. This is how you do a road closure: a few crowd control barriers and a couple of police; no thought of a vehicle-borne attack here. Further on we’re stopped by a young woman asking if we have 5 minutes to spare to help her students practice their English. Simple questions about where we’re from, what’s our favourite colour, what animals do we like. I get a quick history lesson about the Roman Catholic Cathedral too, then it’s time for a photo and they’re off, looking for the next tourist. There’s a sense of 'hurry' but also not. It will take time to find your rhythm. Walk and look up. Interesting cafés and bars are on rooftops. But you have to be game to head down a narrow corridor to find the gem. - Mel |

Mel & Sarah

Currently blogging from home, in iso like everyone else, and catching up with PPC19 in the form of a daily photojournal. Archives

June 2020

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed