Tales of Pacific Pride

Mr Sareth's jail at Bakong Mr Sareth's jail at Bakong It’s 11am on Friday 11 January, and Sarah’s in the shower at our Sydney home, watching red dust from a pre-Angkorian temple site swirl around the chequered tiles and wash away. It’s not our usual homecoming; we’re the kind of travellers who prefer a final shower and some calm, tying up any loose ends before getting on the plane. We didn’t expect to visit any temples this trip; we hadn’t even bought a temple pass. So we’re still reeling from the day before, when a last-minute alignment of stars saw us go from our hotel to Angkor to the airport. Our Sydney friend Diana, in Siem Reap to supervise nursing students, had mentioned to us her friend Hun, a monk at Lolei Temple. Hun runs a school alongside the temple, and Diana thought he might be interested in having a choir visit. We were just finishing our packing and preparing for a spot of gift-shopping when Messenger pinged. It was Diana and Hun, with an invitation for us to visit Hun’s school that afternoon. Diana included a photo of the pre-Angkorian ruins she said were part of Hun’s monastery site. We recognised the reddish stone instantly as belonging to the Roluos Group - a collection of three of the oldest temples in the Angkor complex, and among Sarah’s favourites. We have to decide what to do - is it worth paying for a day pass to visit Hun on site for an hour on the way to the airport, or should we just chat more on Messenger? There’s only one way to do things properly though, and that’s in person. If Hun could make time to see us, then we should certainly make time to see him. And so we did. Mr Sareth, our driver, knows exactly where he’s going. We manage to run a little early, so he suggests we stop at all three of the Roluos temples, starting with Preah Ko, and then Bakong. Both Bakong and Lolei have monasteries attached to them. Sarah is particularly excited to see Bakong again - like most pagodas, the walls of the Bakong pagoda are covered in intricate murals depicting the lives of the Buddha or scenes from the Ramayana, but Bakong is especially beautiful. Mr Sareth pulls the car over near the bridge across the surrounding moat. He turns in his seat to face us. ‘Do you see the big white building there, and the one next to it? Khmer Rouge used them as a jail.’ ‘I know, because from 1978-1979, I was in that jail.’ We already know Mr Sareth lived through the Khmer Rouge. There’s a weird calculation that you start to do, usually at some point early on your first trip to Cambodia, where you realise that everyone over a certain age must be a survivor (unless they were out of the country). We’d both run this internal calculation on first sight of Mr Sareth: a small, nuggety man, well-muscled with a deep smile, he looks healthy and strong, but his hair is definitely greying. Although it took a couple of days, he’d already told us he was in jail under the Khmer Rouge by the time we pull up to Bakong, although he didn’t say where. In a flurry of last-minute changes, we’ve inadvertently brought him right to the doorstep of his own deepest trauma. Sarah thanks him for bringing us here, and we ask how he feels being here now. There’s that magnificent smile again; Mr Sareth shakes his head, taps it sadly and, still smiling, says, ‘Very big problems, in here’. The walk across the moat to see Bakong feels desperately sad. We shouldn’t be surprised by what Mr Sareth has told us - the Khmer Rouge turned every public building, including monasteries, into jails. We look at the murals, and sampeah to Buddha, all within view of the place in which Mr Sareth somehow survived, and countless others died, for no reason and in the deepest horror. Lolei was the last of the three late 9th-century Roluos Group temples to be built. Today, its four temple towers are behind scaffolding. There are monastery and school buildings where Mr Sareth parks and also on the higher terrace which holds the temple. Ascending the terrace, we realise it is surrounded by buildings, none of which we paid any attention to last time we visited. Hun is teaching Chinese to a group of school girls. We’ve never met a Cambodian Buddhist monk - at least not on a first-name basis - and we have no idea how to greet this smiling man in saffron robes, a friend of a friend, but also head monk. Before we know it we’re out the front of the class and it’s swapped from being a Chinese lesson to an English lesson. The girls - all either ten or twelve years old, we learn - shower us with questions, with only a little encouragement required from Hun. Their pronunciation is excellent. Mel attempts to draw a map of Australia on the whiteboard. Then one of the girls asks Sarah if she has a husband. ‘No, no husband,’ she replies. Dorothy McRae-McMahon’s oft-remembered words swim to the surface of our minds: coming out is not a one-off experience, it’s a constant choice. Do we choose to do it here, in the shadow of an ancient temple, standing next to a Buddhist monk, in front of a class of primary-school-aged Khmer girls? ‘I live with Mel. We are married - we can do that in Australia.’ The girls regard us steadily; we don’t know whether it’s their English skills that have failed them, or their comprehension of gay marriage. Hun says something to the girls in Khmer, and internally we both brace for, at best, giggles, at worst, grimaces. ‘I told them this is allowed in Australia, but also in Thailand, and also in Cambodia - free choice. Like in Buddhism.’ He breaks into his trademark grin. We look at the girls; they look back at us. They have complete trust in what Hun’s said. One little girl puts her hands over her heart and, fluttering her eyelashes, sighs as if we’ve just stepped out of the denouement of a Disney romance. Hun and his team of volunteers teach around 300 local school children: maths, English, Khmer, sewing, computers and Chinese. Around 25 orphaned boys board at the monastery. The school, called the Friendship Association for Cambodian Child Hope, also helps local kids with school materials such as uniforms, and even scholarships. Hun himself has a Masters in Economics, is articulate, and giant-hearted; his frequent smile borders on cheeky. He explains how he’s been working with Diana’s clinic - his job is to gain the confidence of patients who have been avoiding much-needed treatment in hospital. Many people struggle on with injuries or illness rather than temporarily deprive their families of a breadwinner; Hun has to help them understand the long-term consequences to them and their families if they don’t take time now. Apart from the orphaned kids in his care, Hun has seven cats (all boys too), and we’re not sure how many dogs. We slither down the ancient uneven steps to the prayer hall at the bottom of the temple terrace. Prayer flags flutter in criss-crossing strands across the ceiling and the walls surround us with brightly-painted scenes of the lives of the Buddha. Sarah sings a few notes but we already know we don’t really care about the acoustics. Hun says there are people in the surrounding villages who he thinks will benefit from hearing us. If he can make it happen, then we’ll sing at Lolei. Mr Sareth takes a back-street wiggle to the airport. At the end of the Khmer Rouge, he had the chance to move to America, but chose to wait in the hope of reconnecting with his family. None of them survived. We think of the family trees of Holocaust survivors we’ve seen, the single line surrounded by the blankness of generations rubbed out. The backstreet wiggle takes us past the little restaurant Mr Sareth’s eldest son and his new wife run. In a month, Mr Sareth will be a grandfather. He tells us about his wife, who only needs to shop at the markets once a week now because she can store everything in the fridge. Also we hear about his other children, all of whom are well-educated and in good jobs. Mr Sareth is doing well; there’s enough money for his family and when he has some left, he takes it back to his village and gives it to the poor people there. By way of farewell, Mr Sareth says, ‘I am happy now.’ We knew we were stepping into unfamiliar territory for ourselves, trying to set up a pride choir tour in South-east Asia. What we know from working with choirs is that behind even the most ordinary-looking of people, there’s a complex and compelling story. Making art together creates a space where some of these stories can come to the fore. We had little idea what we were doing or how to go about doing it when we arrived in Vietnam and Cambodia. But we did what we’re good at - hearing people’s stories - and have met people more brave, more generous, more decent, than you could ever imagine. Our stories and our lives are now linked - so will our voices be, come July. Our 2019 scoping trip to Cambodia ends here. Thanks for reading. To join us on the tour this July, follow the button on this page. To donate to Hun's school, click here.

0 Comments

‘Your driver is here,’ says one of the hotel staff as Sarah enters the foyer on Wednesday night. ‘That’s not our driver,' says Sarah, 'that’s our friend.’

Naga Cambo, our tuk-tuk driver from three years ago, has arrived to take us to dinner. We greet each other with a sampeah. There are five levels of sampeah, all involving a bow: for friends - palms together at chest level; for older people or people of rank - palms together at the mouth level; for parents, grandparents or a teacher - palms together at the nose level; for the king or monks - palms together at the eyebrow level; and lastly praying to Buddha or sacred statues - palms together at the forehead. So it’s a nice surprise after the formality when Mr Naga follows up with a hug. It’s good to see him; it’s been two and a half years. May 2016: we arrive for ten days’ holiday in Siem Reap. Our first trip in 2009 gave us a taste for temples off the beaten track; they have few tourists and little, if any, restoration. Whilst you have to see Angkor Wat and the Bayon complex, these lesser-known temples are our favourites. We’ve scoured our Lonely Planet and have made a list. Through the Rambutan, we’ve arranged for a tuk-tuk to collect us and take us to our hotel. Whilst only 6km from the airport, as Deborah said to us recently, 6 kilometres can seem like 20, when your top speed is 38.5km/hr. It’s blisteringly hot and searingly dry; smoke hangs low in the air and the light is an eerie, dirty orange. Forest fires, Mr Naga tells us; people are burning the land to clear it. It’s only mid-morning, but whilst we’re feeling quite refreshed having overnighted in Bangkok, we’ve not really put a plan together. We have a list of about forty temples and a vague idea of half a day of temples, half a day by the salt pool, cooling cocktail in hand. So, even though we’re not that keen to revisit temples we’ve seen, that afternoon Mr Naga takes us back to Ta Prom (made famous by Angelina Jolie in Tombraider). The last time we were here, it was midday, stinking hot, crawling with tourists, and being renovated: the sound of chainsaws was deafening. This time, it’s much more tranquil. We're also on the hunt for the stegosaurus carving. No one knows why or how amongst elephants, turtles, apsaras and deities, there is a single stegosaurus carving (and plenty of people say it’s not a stegosaurus at all - but we reckon it is). From that first stop, ten days of really getting to know the temples, and Mr Naga, begin. We discover Naga also does moto tours when he only has a single patron, and he’s actually taken some quite intrepid travellers to some very remote temples. On the second day, he looks at our list and tells us he’ll take us somewhere more interesting. At first we’re sceptical - we’ve done our research - but after a particularly obscure detour he pulls up at the foot of a towering mound of ancient collapsed brickwork. This is Chau Srei Vibol, and we’re the only visitors. There’s an elderly man who speaks no English roaming the site; he leads us around the leaning pillars and lichen-covered stones held up by strangler figs. This is the kind of experience we’re still a little nervous about, but we get used to it as the trip unfolds. Naga usually lets us know in advance if there’s a self-appointed local guide. Some of these temples are remote, and in a country with limited social security, a dollar from a tourist can make a real difference to someone elderly or disabled whose work options are limited. At Chau Srei Vibol, we quickly became very glad of him, the warnings not to stray off known paths due to landmines in the back of our minds. In the end, we saw 44 temples in 10 days. We climbed 635 steps to reach Phnom Bok, a mountain-top temple with killer views but whose real magic came from the ancient frangipani trees, sprouting gnarled and massive out of the two temple pillars. We trekked up the river bed at Kpal Spean, River of a Thousand Linga (sacred penises), sharing our stash of rambutans with Mr Naga’s friend the policeman who guarded the site. When we told him how much they cost per kilo in Australia, he had hysterics. And we fell utterly in love with Beng Melea, a massive complex which combines the scale of some of the Angkorian temples with the lichen-and-fig wilderness of Ta Prom. We saw more yoni and linga than we could count, stone representations of sacred genitalia, the lips and mouth of the yoni always pointing North, although nothing could top the massive two metre yoni-linga carved out of bedrock on the ring-road out to Koh Ker. It's late afternoon and we're coming to the end of time here; we've just about exhausted our list of temples. As we clamber into the tuk-tuk, Naga turns and asks, 'One more temple? It's on the way back'. Prasat Kravan is a small 10th-century temple consisting of five reddish brick towers. We've driven past it numerous times, both this trip and the last. It wasn't on our list and doesn't look too remarkable from the roadside. At about 5pm, the sky is turning dusky pink; a combination of the sun's weakening rays and smoke from the forest fires which are still burning. The light reflects off Kravan's façade, dramatically enhancing the hues of the red brick. It looks spectacular at sunset. Sensing we're not quite in love yet, Naga advises that we need to go around the back. The temple is dedicated to Vishnu, and the interior of each of the five towers shows large bas-relief images of the god and his consort Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, prosperity and fortune. The carvings are exquisite, some of the best preserved we have seen, as is the Sanskrit which is carved into the posts at the entrance to each tower. Amid the bustle of the Angkor complex, Kravan keeps her quiet secrets, but not from Naga, and no longer from us. He's brought us to his favourite temples, Kravan included, as well as a butterfly farm, to various craftspeople, into the market where he bought his own wedding clothes, as well as countless good places to eat. He's helped us buy forest fruits by the roadside, as well as stuffed frog, and convinced us to try prahok, a fermented fish paste. At this point in his life, Naga hasn't yet become a tour guide - that's still to come - but he's shown us ten days of wonders. If we can help our travellers see even a little bit of the Cambodia he's revealed to us, then everyone will leave this place at least a little bit in love. Naga Cambo: limyiv @ yahoo.com (+855) 92 402 400 A woman, fierce and fluid, is dancing to Tom Waits and a shrieking angle-grinder. She moves through spangled golden light: builders’ dust, caught in the strong Cambodian sun which pours through the open doors at the back of the theatre. We’ve driven through dusty backstreets to find this place, the first black-box theatre in Cambodia, purpose-built for contemporary dance company New Cambodian Artists. The six-year-old, all-female troupe embraces the empowerment of women through expression, but after everything we’ve seen, we’re not prepared for Tom Waits.

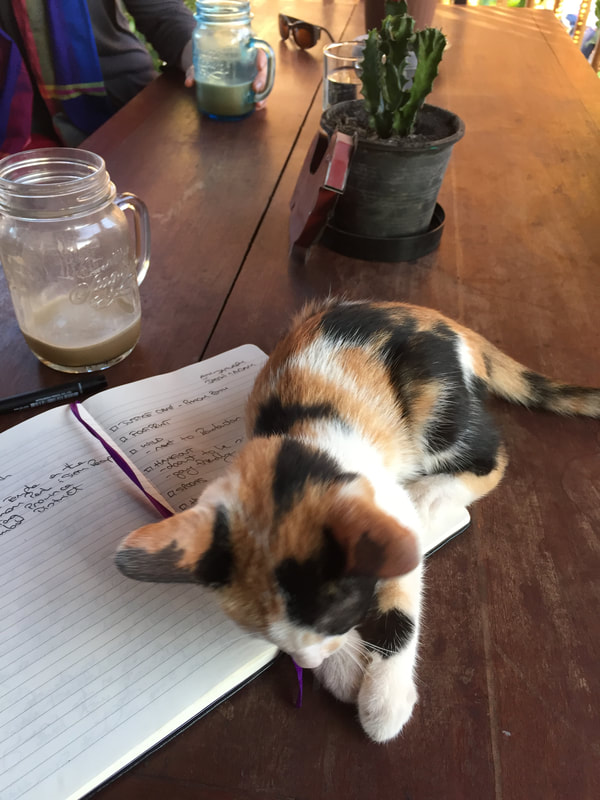

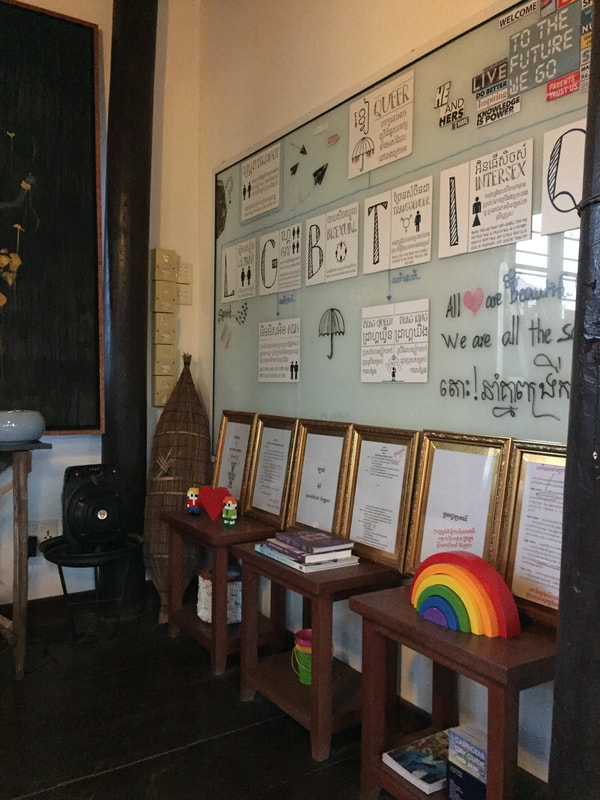

‘The girls have been choosing their own music,’ choreographer Bob Ruijzendaal cheerfully explains to us, over the whine of the machinery next door (company manager Khun Sreyneang is finally getting her own office - which she has had painted a good feminist lavender, her favourite colour). ‘We used to do this routine about death to Arvo Pärt, but then one of the girls brought in this song - now we have a whole Tom Waits set!’ And indeed they do - it is by turns haunting, beautiful, darkly funny, and sad. Bob is enthusiastic about the dancers and Sreyneang, and he has a lot to tell us about the company’s attempt to do something new in Cambodia, to challenge traditional roles and forms of expression for women, and to create true professionals with their own marked artistic identities. Bob tell us the women’s individuality and strength is often criticised as arrogant in the Cambodian environment, but he says they’re not arrogant, they just know who they are. We’re fascinated, but the women have clearly heard it all before and only want to get back to their dancing. There’s a seriousness, an edge to this company and these women that’s thrilling to be near. What a pity we’re not here for one of their regular Saturday night shows. It’s been a day of privileged glimpses backstage. Our Wednesday morning began in a familiar environment - the Rambutan Siem Reap, to catch up with General Manager Tommy Bekaert. We’re keen to get his insights into the local LGBT scene. We stayed ten magic days here in 2016, but this time we’re learning about life from Tommy’s point of view. This trip, more than ever, we appreciate that the Rambutan staff have excellent English. Tommy tells us that university training is on offer for all their staff. There’s a common career progression: Khmer with no English start as night-time security so they can study English during the day. After a couple of years, they graduate to the breakfast team and continue their daytime studies. A couple more years and they’re ready to move into any one of the other positions - the welcome team, administration, etc. Rambutan’s newsletter is always announcing the graduation of some staff member or other from university, not just with English, but degrees in hospitality or business. Tertiary education in Cambodia is generally paid for by the student - government scholarships are available, but only for the brightest. No wonder the Rambutan staff are so loyal and the place feels like a family; people are here for the long haul. And they throw a mean Pride pool party as well. We’re reluctant to haul ourselves out of the Rambutan’s comfy couches but our next stop is the Bambu Stage - really a series of stages, purpose-built and flexible for a variety of shows (and meteorologies). Visiting Bambu Stage in the daylight is like going backstage in a theatre; all the ropes and pulleys, usually masked by darkness and leaping firelight, are naked to the eye. Nick Coffill - another Aussie - emerges from one of the many clumps of bamboo shielding parts of the property and apologises disarmingly for his theatre’s daylight garb. He shows us round the ingenious set-up and the various configurations to accommodate everything from live music to shadow puppetry, to fine weather to storms, small crowds or large. We learn about the company structure too; places such as Bambu Stage provide forums both for traditional Khmer art to survive and platforms for new Khmer art to develop, all while paying the artists some kind of wage. Nick is a veteran producer and a half hour’s conversation with him turns up several interesting venues around town, including New Cambodia Artists’ purpose-built theatre. There’s also the Centre for Khmer Studies in Wat Damnak. Nick joins us to visit it, directing our driver Mr Sareth in what sounds like the most fluent Khmer we’ve heard a westerner speak so far. His love for the Wat and appreciation for the instant peace its grounds bestow is evident. We feel the same way, and are grateful for his help as he introduces us to the staff at the Khmer Studies Centre and gains us entry to their conference hall, a modest French colonial building on the grounds of the Wat that would make a choir sound like a million bucks. Nick is the only expat we’ve met who hasn’t spun us a romantic tale of love-at-first-site with Siem Reap, wielding instead a more cynical outlook, but we can tell his respect for the place and its people runs deep. We think of the planning permissions that would be required to construct a new stage or performance space in Sydney, of the years it would take and the money it would cost. Performers like the New Cambodian Artists will spend the bulk of their developmental period in a space purpose-built just for them, by people who seek to plug the many gaps in the artistic market since the Khmer Rouge. And they have stories to tell; the question remains, will the world listen?  Wat Damnak, site of Cambodian Living Arts' Heritage Hub Wat Damnak, site of Cambodian Living Arts' Heritage Hub Tuesday is a day for double-dating. Apart from our two dates with the LGBTQI community, we also have two dates with arts groups in Siem Reap, at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of size and reach. The first is with Kai from Cambodian Living Arts, who Mel met at the Bambu Stage on Sunday night. He’s invited us to the Heritage Hub at Wat Bo, an old Buddhist monastery and pagoda in the middle of town. We start by watching an Ethno-Cambodia workshop - for one week, 30 young musicians from around the world, all playing traditional instruments, have come together to teach each other their music. By mid-afternoon they’ve already learned three songs (apparently the Swiss piece was a bit of a challenge for some of the more microtonal instruments), and it’s currently the turn of the Indian team to teach. There’s an amazing array of instruments in the room; some we recognise: drums, guitar, violin, traditional Cambodian instruments and a Japanese sho. There are also five singers. The Indian flautist plays his piece phrase by phrase, each musician learning by ear, some copying tentatively, others with evident gusto. Some annotate small notebooks. The singers have moved to the stage area to learn their part. If they were after quiet, they won’t find it here. You need to be a quick learner in this environment as each teacher only has about 30 minutes. Looking at the different instruments, we wonder how this piece will ever come together, particularly as the tempo dramatically increases. One player, on what appears to be a single-stringed instrument, looks pleadingly at the teacher: 'It's hard to go faster on this instrument, perhaps a little break between verses would help?' But by the time Kai returns for us, the Indian piece is rocking along. Sarah in particular is blown away by the concept. Kai has much more to share with us, though, including the story of Cambodian Livings Arts, whose founder survived the Khmer Rouge by being quick to pick up the national songs they gave him to play. After the regime’s end, he found Cambodian traditional music had disappeared - those musicians who had managed to survive couldn’t make money from their art and had abandoned it. So began CLA’s long quest to rebuild Khmer art and create a living for artists. The female drumming group Medha is just one of their ensembles, and they’re also currently helping the Khmer Magic Music Bus, which travels to rural areas to demonstrate and teach traditional music to kids. (A bit like our Musica Viva program but with a cooler name.) Kai has plenty of suggestions about places we could perform, including at the Heritage Hub, and artists who might perform with us. Personally we love the idea of putting a Rainbow Choir on a Magic Music Bus - it sounds like Enid Blyton meets The Wiggles - but we’re not sure we’re quite the target market! We are definitely at home with our next music appointment however - 6.30pm is time for choir! Yep, you heard right, we’ve actually found a choir in Siem Reap. They’re called the Siem Weep Singers, and they’re run by Deborah Saunders, another Aussie ex-pat who upped stumps and moved here over ten years ago. The choir is currently a small group of expats who get together on a somewhat ad hoc basis to sing easily teachable world music and popular songs. They’re always keen to welcome new voices and tonight, we’re bringing three. In a sign of what a small world it is, Sarah’s friend Diana is also in Siem Reap, supervising nursing students. Sarah and Diana met and bonded over Old and Middle English in the mid-2000s when both writing their PhDs, and have run into each other randomly at Sydney Philharmonia rehearsals where Diana sings and Sarah’s on the roster as an emergency conductor. We’d all planned to have dinner, but Diana is up for a sing before supper, so she joins us there. The Siem Weep Singers (glad to know a good choir pun is an international phenomenon) is a small group of women. The nature of contract work here means that people come for two years then leave. Again it’s a familiar theme. Adam told us earlier that you have to work at staying connected in Siem Reap. People come for two days, two weeks, two months or two years, but after that, they usually move on. We’re welcomed warmly. What a refreshing change from Sydney where it is can be so hard to break into a new group and feel instant rapport. With three extra singers tonight we just about double the size of the group. We sit at a small kids’ table with an array of instruments including a ukulele, bells, and maracas. The group rehearses at the Small Art School, a self-financed art school providing free art education to Cambodian children. The associated gallery sells the kids' artwork and the money raised is split three ways between the artist, gallery operating costs and funding for the education program and art materials. Through this work, not only is the gallery the providing kids with an opportunity to make a living from their art, it’s also providing them with much needed business skills. The plastic choir folders are bursting with songs and lyrics. Over the years those who have joined have left songs to add to the collection. Deborah plays the ukulele and sings all the parts for us to copy. We have quite a few songs in common; maybe the Siem Weep Singers can join us for an item in July? We have great fun, and puppy cuddles from wrinkly little Tulsi, choir member Nicole’s seventh adoptee (she volunteers at one of only three vet clinics in town). Sarah’s invited to leave a song with the group and teaches Freedom Train. After dinner together at the local Thai, Deborah drives us home in her red-and-white polka-dotted tuk-tuk, christened ‘The MAD-Dame Mobile’. Anyone looking for a song in their heart and a spring in their step in Siem Reap should look her up.  Jason & Freddie at A Place To Be Yourself Jason & Freddie at A Place To Be Yourself 10am Tuesday, and we're sitting in an Australian-owned, Cambodian-run cafe, The Little Red Fox Espresso, reportedly the best coffee in Siem Reap. We’re meeting Jason Argenta, founder of A Place to Be Yourself, a drop-in centre and safe space for LGBTIQ+ people. Originally from Perth, Jason came to Siem Reap about five years ago, volunteering to build houses and to teach. He loved working in the villages building houses, and quickly discovered that teaching wasn’t his thing. One month after his holiday to Cambodia and then Europe wrapped up, Jason had sold up everything he owned in Australia, to move to Siem Reap on New Year's Day. This is a theme we’ll hear repeated again and again by the surprising number of Aussie expats we meet - come for three days, never leave (PPCers, you’ve been warned!). With qualifications in Psychology and Sociology and working in Child Protection, Jason had volunteered at an LGBTQI drop-in centre in Australia. But as we’re discovering, there is something about Cambodia and Siem Reap in particular which draws you back. After selling everything, he moved to Siem Reap, and seeing a similar need, founded A Place to Be Yourself (APTBY). Surviving on fundraising and the odd contra arrangement, APTBY is open three hours every afternoon and employees two local Khmer staff: Pov, a trans man and Kunthea, a former street kid. Their office is on the first floor of the Purple Mango Wellness Centre, a typical Khmer stilt house, and offers a range of services including sexual health information, free condoms, and free counselling. On the covered deck, next to a spreading mango tree, lolls Freddie the genderqueer cat and his new kitten sidekick, Fanny. Despite the multitude of resources on the walls, the place feels instantly like home. An 'identity wall' spells out LGBTQI with Khmer explanations beneath. Both Jason and Pov explain that this is the best way to introduce these terms and concepts. People accessing the space can read the wall in their own time and then ask questions. In fact, this is how Pov came out as a trans man. He identified as Lesbian, but after having the identity wall explained to him, and the term Transgender highlighted, Pov walked away a new man. Not only did his life make sense, he knew he wasn’t alone. Pov came out to his family and it was difficult for his parents in particular to accept his choice. But after three years, his father finally said, 'You are my son.' Khmer people are traditionally gently-spoken and reserved, but there’s still raw emotion in Pov’s face and voice describing this seminal moment. Our day segued from the Little Red Fox to A Place To Be Yourself in much the same way as this blog post - what started as the best coffee in town with Jason, made by Adam’s expert LGT cafe staff at the Fox, has morphed into coconut coffee made by Jason at APTBY while Adam snidely offers barista training if he needs it. There’s a clatter from the kitchen in response as Adam, a Brisbane bloke who also threw in his Aussie life for Siem Reap, regards us cheekily over his bushy hipster beard. Both Jason and Adam are part of the network of LGBTQ business owners who organise Pride and other events in the town. We’ve hit the motherload of queer intel and by the time the sun is setting, and Freddie and Fanny reduced to rapturously purring puddles in our laps (make up your own jokes, we certainly did), we feel like we know every business and business owner, and how they fit into the rainbow jigsaw puzzle, even if we won’t manage actually to visit every establishment. Suffice to say, despite the massive boom in every kind of shop and eatery you can think of, you could stay here a good while and only support the pink economy if you so wished. It’s heartening to see how many of these businesses employ, partner with, or are run by, Khmer. Pov takes a photo of us standing under APTBY’s emblematic rainbow umbrella, each of your two pet-sick authors cradling a very compliant cat. It’s still amazing to us how easy it is to feel like old friends on first acquaintance with fellow queers, and how living a common experience of exclusion (despite obvious differences in degree) can break down language barriers to create an inclusivity that defies international borders. A Place To Be Yourself - isn’t that something we all could do with? On our third visit to Siem Reap, this more relaxed major city feels pretty familiar, but at the same time, as in Phnom Penh, the pace of change has clearly been fast. New malls and shops have opened, and there are a lot more pockets of upmarket and at times glamorous shops and eateries. Cambodia’s artistic and cultural capital is clearly on trend - even iced coffees served in jars at cafes with paleo menus have sprung up and are thriving.

Siem Reap is the final destination for the tour later this year, so we’re checking out the hotel and again, meeting with local LGBTQ groups and arts organisations with whom we can partner. We travelled overland from Phnom Penh by car instead of flying. It’s s great way to reacquaint ourselves with the land. The outskirts of Phnom Penh have seen a boom in the housing market. Many acres of land (once rice fields, we assume) have been turned over to identical series of grand, white residential apartments. We wonder who the target market is. Soon after, the familiar rice fields appear, the lush green stems swaying gently in the breeze. It’s Sunday, so no school today. Seems that it may be the only day of rest here for many, although the villages buzz with life and every shop is open. It’s a good day for weddings, and we pass over a dozen; you hear them before you see them, traditional music blaring from tinny speakers. Coloured marquees are set on the edge of the dusty road, chairs with elegant covers arranged within. Women in shining traditional dress arrive on moto, wrapped in casual shirts to preserve their sparkling attire. We stop briefly at the Spider Market. Yes, they sell spiders - great platters of fried ones, big black hairy critters pulled by hand from burrows in the hills. But if spider isn’t your thing, not to worry -there’s deep fried cricket with fresh chilli. The rice fields now are dotted with palm trees; a further sign that we are heading north. The roadside street stalls have changed too: stall after stall of sticky rice. These stalls, more than anything, remind Mel of Siem Reap. The rice is packed into tubes of bamboo (which serves not only as a cooking vessel, but also a compostable takeaway container) and cooked over charcoal. To eat, simply peel the bamboo away. It’s a delicious snack. Just before 2pm we arrive at the Angkor Paradise; our palatial hotel has a light, open foyer, polished granite floor and solid Khmer timber furniture. The staff are immaculately and formally dressed, but welcoming. We feel very underdressed and slightly grubby after our overland trip from Phnom Penh. We’ve been upgraded to a room on the Paradise (5th) floor. There’s plate of fruit and welcoming note from the General Manager. Note to self: dress more appropriately next time... Tonight we’ve been invited to the soft launch of a new show, 'The Call', by drumming group Medha, a new show produced in conjunction with Cambodia Living Arts. This all female drum troupe is seeking to break gender stereotypes in a country where drumming is seen as a male pursuit. Our names are on the door list and Mel is met by Nick Coffill. Hearing my accent, he says, 'You’re not from Sydney, are you? We don’t let people from Sydney in.' It’s clear by his accent and the cheeky glint in his eye that he too is Australian, from Condoblin, in fact. He suggests that Mel pretends to be from Canberra for the night. Nick's been in Siem Reap for six years as Creative Director of the Bambu Stage, a performing arts platform providing a space for artists and puppeteers. He’s interested in our project, suggesting that choirs are needed here. The arts scene in Cambodia was one of the many things destroyed during the Khmer Rouge, and Bambu Stage is one of the many arenas through which artists both Khmer and international are attempting to rebuild it. Bambu Stage is especially interested in Khmer art; of the three stages, one presents a puppet show, with puppets made onsite. There’s no program to go with the night’s performance, but you don’t need to understand Khmer to understand the unfolding story, told though drumming, singing and traditional Cambodian instruments including the korng vong thom and roneat (resembling gamelan instruments). The six women contrast traditional drumming with explorations of modernity: individuality, social isolation and claiming a space for female artists in non-traditional roles. The impression that women playing these particular traditional instruments is transgressive is clear from the moment they take the stage, as is their joy in performing. It’s a refreshing blend of theatre and music, contemporary and traditional, that wouldn’t be out of place at one of the globe’s better fringe festivals. And it’s right here in Siem Reap - after such a successful evening, we hope to see many more shows from Medha. Everywhere we go the message is consistent: things are relaxing here and the economy is moving. With more money flowing in to the country, there are more opportunities for people. Skyscrapers are appearing on the horizon; shiny investment bank buildings and hotels are springing up. But poverty is still a huge issue, as our meeting with Srorn showed us.

There seem to be two types of businesses here too. Those like Blue Chilli which carve out a space and thrive, and those that look like fantastic start-ups and sputter into life only to close their doors after a couple of years. Today is a hit-and-miss day full of just this kind of contradiction. We're looking for alternate venues for our performances in Phnom Penh and have a list of gallery spaces to view. We’ve got the list sorted and hope that our patient driver, Mr Viriya, finds us more organised today. META House looks promising. Opened in association with the International Academy at the Free University of Berlin, it boasts three floors of gallery space and a media lounge. The open upstairs area would seat around 50. The downstairs gallery is small and currently hosting an exhibition centred around environmental awareness. This seems to be the biggest change in the ten years since we’ve been here: a growing awareness of our impact on the planet. Our hotels offer free water re-fill stations (important in a country where the tap water isn't drinkable) and there’s a move away from plastic straws. Some shops use paper bags made from old newspapers with string for handles. No middle-aged white people here, demanding their right to a plastic bag. Surely it can’t be that hard... As part of her Make Art Not Waste project, Nina Clayton’s 'Ocean Cry' echoes the thoughts of many of us. It’s made from plastic refuse collected from the beach. Another work is a perspex box (60x30x40) full of items the artist has consumed in a five-month period: medication boxes, foil blister packs, cigarette boxes. It makes you stop and think. Despite providing food for thought, META House isn’t going to fit us, and the next two galleries are permanently closed, although their websites look up-to-date. (Pro tip - always double check on Facebook., ubiquitous in this part of the world). Mr Viriya is patient, but we sometimes wonder what he makes of all this. The cool and spacious French Institute of Cambodia looks more promising. There’s a gallery with several rooms of a beautiful exhibition by Caroline Chevalier and students, and an outdoor courtyard. It’s also close to the bridge over the Mekong so would be handy for Sanh and the trans community, provided the venue is one they’d be comfortable in. A certain level of informality is the best way to engage the biggest cross-section of LGBT in this part of the world. The administrative offices across the road have a huge sculpture of a bull on the sidewalk made almost entirely of bicycle chains. But it’s this evening, our last night in Phnom Penh, that we’ve really been looking forward to. We’re off to Counterspace Theatre at Java Creative Cafe (one of three in Phnom Penh), thrilled that Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA have a show on the weekend we’re in town. Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA is Cambodia's first gay dance company. We’ve been following them since they popped into our inbox in one of Rambutan’s newsletters, 3 years ago. The fledgling company's website describes it as re-staging: ‘Khmer classical dance with a vital freshness to create original, groundbreaking works at the intersection of art and human dignity. The dancers seek to infuse their tradition with a contemporary spirit, elevating the quality of life and expression for LGBTQ people in Cambodia and beyond.' Prumsodun himself, the choreographer and creative behind the company, is a child of Khmer refugees, born and raised in the United States. Classically trained, he wanted to become an Apsara dancer ever since he first saw this female art-form on a family home video at the age of four. He describes how his Khmer colleagues tried to persuade him to return to Cambodia. Initially he refused, thinking he couldn’t bear living in a country and among a people he loved but not be able to do anything to salve the poverty and hardship. Apsara dance is over 1,000 years old, and, with over 1,500 hand gestures alone, young girls commence training as early as five years old. It’s a complex art, requiring great flexibility of the hands and feet, which makes what we have seen tonight all the more powerful. Of the six dancers on stage, five of them commenced their training in Prum's lounge room only three years ago; the remaining cast member is Prum himself, who started his training in late high school when his sister’s Khmer dance teacher agreed to train him. The hour-long program features four classical dances, an excerpt of Prum’s own show BELOVED, and a contemporary dance duo to Sam Smith's 'Lay Me Down’. The three apsaras who first appear on stage are familiar to anyone who has seen Khmer classical dance - except their chests are bare. This is the only trait revealing their maleness; otherwise, they are as exquisitely dressed, made-up and delicate in movement as their female counterparts. The performance explores both gender fluidity and homoeroticism, with the soundscapes to the excerpts from BELOVED including sensuous poetry along with a dance narrative full of longing and desire. The contemporary duet between two young men manages to be both beautifully executed and vulnerable and raw; the nerves of young love, overlaid with possible fear of rejection (by the beloved? by family? by society?), tremble in every movement. At the end of the show, Prum tells us that classical art is about representing heaven, where all things are perfect and beautiful. He asks what it says about a society when its vision of heaven has no place for you - if there are no gay men represented in heaven, what can it mean except you have no place there: you are nothing; you are dirt; you are unworthy? Prumsodun & his troupe's work in carving a place for gay men in the heaven of Khmer classical dance is claiming an equal space for gay men in Cambodia; another testament to the power of art to create change. If you’re in Phnom Penh, see this show. It’s not often we wake up the same day that we go to bed ... we're old lesbian nanas who don’t go clubbing and so in the words of the late Aunty Mark, we should 'hand back our gay cards'. But not tonight. Tonight we’re ‘taking one for the team’ and going to a drag show.

Since we first came to Cambodia 10 years ago, the one constant in the gay scene has been the Blue Chilli. Established by Sokha Khem in 2006, it’s now an institution. Sokha was born in Svay Rieng province, and grew up as a farmer. His family and village were poor and he didn’t feel that he had a future there. He moved to Phnom Penh and did all manner of jobs: moto driver, cement worker, charcoal maker, even working for an NGO. With a bit of luck, and support from friends, he established Blue Chilli. 12 years on and the bar and the LGBT scene here has changed. We’re welcomed warmly by the staff. The music is pumping and we sit outside where it’s comfortably loud. It’s at least an hour until the hour-long drag show, although we do wonder if the rumours are true and we might be running on gay time tonight. It’s mostly gay men, but we don’t feel uncomfortable or out of place. Sokha is talking with patrons and finds his way over to us. He starts to tell us about the establishment of the bar and how the LGBT scene was very different then. 'Now', he says, 'it’s more open'. He too laments the demise of the lesbian bars in Phnom Penh and confirms our theory that lesbians aren’t really big on the nightclub scene. There are three drag shows a week by young artists. Sokha’s working with a new designer and the new costumes should be finished in about two weeks. He’s expanding the shows to five nights a week. He's philosophical about how it will all pan out, particularly mid-week when people do need to work the next day. More people arrive, including some straight couples, who wander inside, turn around, and wander out again. 'Not the target market,' quips Sarah. Others stay; this is clearly a place where everyone is welcome, provided you’re comfortable running the gauntlet of beaming young men waving chilli-shaped menus (it’s not such a hardship, even two middle-aged lesbians like us find them adorable). Surprisingly close to the advertised start time of 11pm, the music inside changes and everyone starts to press in towards the small stage. Showtime! For an hour, we are captivated by a series of young artists. The girls (and their two hardworking male sidekicks) can really dance. There are no grotesque parodies of womanhood in the dance routines, just a lot of joy, heart and skill (props to the queen who danced across the bar in towering red patent leather stilettos and vaulted back to the stage from the bar top at the end of her routine). It’s refreshing to be in a gay bar where everyone feels so comfortable, you don’t stick to the floor, and there’s no queeny cattiness to stick to you. Only one age-related gag at the expense of the queen who turns out to be having a birthday, but all is forgiven when a tiny cake is handed up to the stage and she starts to cry, jeopardising her magnificent eyelashes. We’re almost too engrossed to notice the bar is absolutely packed and heaving by the show’s conclusion. Blue Chilli’s clearly not going anywhere, but, as the routines end and the first ABBA of the night starts up, we sure as hell are. Tuk tuk! Dirk has told us that it’s winter in Cambodia ... hmmm, perhaps not today.

Ever the optimists, we dressed early this morning in our best 'tidy blue', today's colour according to traditional Khmer dress. After a bowl of tasty soup for lunch at the Russian Market we are dripping with sweat and less than tidy. We’ve got an hour and half until our meeting with the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights (CCHR). We call our driver and head back to the hotel. A quick swim, back into the tidy blue, and off we go. CCHR is a non-aligned, independent, non-governmental organization that works to promote and protect democracy and respect for human rights throughout Cambodia, including Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression rights. We fill CCHR representatives in on our project and who we’ve met. The discussion is wide-ranging. Interestingly, LGBTIQ people in Cambodia face numerous forms of discrimination, partly because of a legal framework which denies them basic equality. In particular, LGBTIQ people in Cambodia face four main forms of legal discrimination, including the lack of legal protection against discrimination and violence against LGBTIQ people; the absence of legal recognition of self-defined gender identity; the absence of marriage equality in Cambodian law; and the denial of full adoption rights to rainbow couples. CCHR representatives confirm what we knew from our previous trips here and what Srorn has reinforced with us. Family is everything, as is community. Many young LGBTIQ people have felt that they needed to leave their homes because of their gender identity. For this reason, CCHR representatives tell us, Cambodian LGBTIQ people identify marriage equality as their most pressing desire. The institution of marriage is exceptionally highly-valued in Cambodia, and excluding LGBTIQ people from the institution of marriage excludes them from one of the foundations of Cambodian society. Our telling of Pacific Pride Choir’s foundation story and the history of LGBT choruses around the world is growing more concise. Our mission this time is different to 2017, and yet strangely similar. Different, purely because choirs just aren’t a thing here. Similar, because most people have some kind of family and most of us in the LGBTQI community have experienced discrimination, whether from family, religious institutions, schools or places of work. These are universal themes. In our singing we hope to create a space for others to join and share their stories, to know that they are not alone. CCHR representatives listen and seem comfortable with our ideas, glad that we’re consulting with different local groups and that we want to collaborate. They help to put us in touch with other players, and mention the recent event 'Our Lives, Our Rights' organized by Rainbow Community Kampuchea (RoCK) to celebrate their 10 year anniversary and the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at The Mansion (Foreign Correspondents' Club), a venue we’ve arranged to see later that day on Srorn’s suggestion. While we’re grateful to live where we do, it’s clear that we Australians have a lot to learn from LGBT activism in South-east Asia. It’s 7.30am and we’re at breakfast already, ready for the day. Those of you who know us know that there is no way that we are ever out the door at this time of the day, despite getting up early. But here we are.

Since yesterday Sarah has been messaging Srorn about a purchase for the members of Pacific Pride Choir. There’s a Facebook Page, Rainbow Cat (Rainbow Cambodia Advocate Team), founded to support the human rights of everyone, not just LGBT as it is known here. They support social enterprise and provide funding to help the poor and the disadvantaged start small businesses. As little as $100 USD can fund a street seller. Srorn tells about Pheng Sahn, a trans man who lives across the Mekong River. Seems there is quite a trans community here. Sahn is a weaver and weaves rainbow kromer, the traditional Khmer scarves, to support his family. We see photos of the stunning fabric. Sahn and his female partner have been together since 1979, says Srorn; before Sarah was born (‘only by a year,’ says Mel). We’d planned to buy a couple of traditional kromer for ourselves and had been going to look for them in Siem Reap. We know a guy who knows a guy who sells them and another who will hem them. Quick change of plan. We do the maths and run the logistics (getting the kromer, getting them back to Sydney and then over to Hanoi), as both Srorn and Sahn are heading off on Friday to tour to Prey Veng, where Sahn will speak to the village community about his life as a trans man as part of the My Voice, My Story exhibition. We order 35, enough for each member of the 2019 tour and a few extra. Facebook Messenger is a wonderful tool (can’t believe we said that). We place the order and Sahn will arrive Friday at 9am with the scarves. Activists like Srorn and Sahn don’t have salaries for their work. Our purchase will fund their families and their advocacy. The softly-spoken Mr Bee and his colleagues at Rambutan help us translate for Sahn when he arrives on his moto. He recognises Rambutan as the site of last year’s Pride Pool Party. Mr Bee is nominated by his co-workers as ‘the photographer’, and so he artfully arranges our kromer and snaps away, posing our hands in the symbol for ‘love’. He shows us another way to wear kromer on his phone: in a photo an exceptionally buff young man reclines on his side, framed by blue sky, wearing nothing but a vibrant rainbow kromer wrapped sarong-style around his groin. ‘This is me,’ shy Mr Bee has to point out to us. As we leave for the day in Mr Viriya’s gold Lexus, complete with wicker heart dangling from the mirror, Sahn and the Rambutan’s gruff butch security guard are hanging out together out front, clearly old friends. We’ve learned something new about two of the Rambutan’s staff this morning, all thanks to rainbow powerhouse Sahn. |

Mel & Sarah

Currently blogging from home, in iso like everyone else, and catching up with PPC19 in the form of a daily photojournal. Archives

June 2020

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed