Tales of Pacific Pride

|

The alarm is set for 8am. No morning meeting means a rare sleep-in. Nevertheless, we're awake before the alarm. No matter; there’s time for a swim and a leisurely breakfast. This morning we’re off to the Vietnamese Women's Museum. It’s been on our radar since friends told us it’s a must-see.

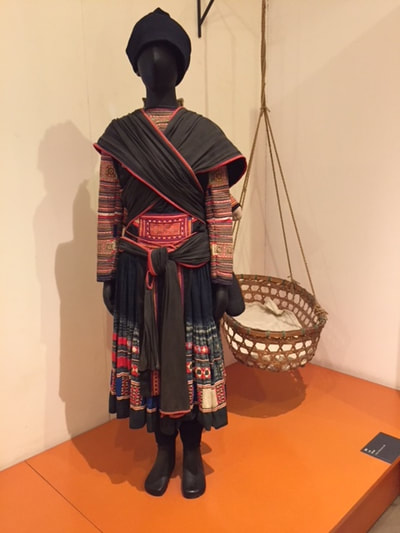

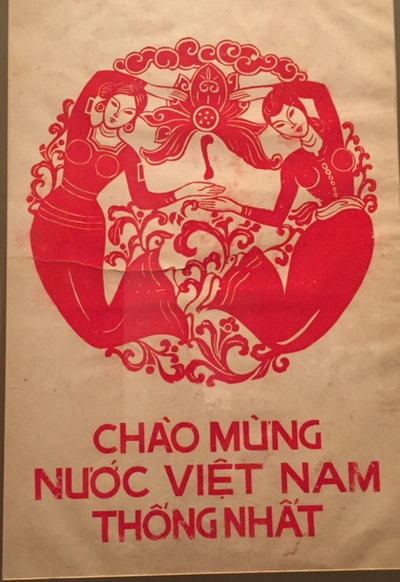

In the foyer, there’s a tall gold statue of a woman surrounded with pink lotus flowers; large portraits of elderly Vietnamese women spread to the left and right, their wizened faces full of a thousand stories. The permanent exhibition focuses on the role Vietnamese women played in the country’s history, and the role they currently play in society and family life. The museum's stated mission is 'to enhance public knowledge and understanding of history and cultural heritage of Vietnamese women ... thus contributing to promoting gender equality.' There are 4 permanent exhibitions: the first, Women in Family, looks at marriage. An information plaque makes it clear that much of Vietnam has always been a patriarchal society. However, some regions were matriarchal, and on marriage it is the man who leaves the family home to join that of his wife. Together we spend much time in the room about the Mother Goddess, discovering that the rituals belonging to her worship involve spirit mediums who channel incarnations of various deities. Like the mediums themselves, deities can be of any gender, creating an interesting space for gender fluidity as the mediums change between them. Mel would have been happy to spend hours in the room devoted to Women in Military. Soft, slightly out-of-focus black-and-white photos of beautiful women adorn the walls. Attached to each is the a story of a young woman, 18, 20 at the most, who served during the resistance wars against a multitude of enemies: a spy working behind enemy lines, a courier, a doctor. These women fought and in some cases died during the Vietnam War. Others spent years in prison, subjected to unspeakable torture. Sarah watches a short film on street vendors. We’ve seen them daily, pushing bicycles with baskets of flowers or fruit; others with a pole balanced on one shoulder, large woven platters on either end piled with smaller fruits and other foods. We’ve not bought anything from them, stopping for meals but not snacks during our trip. 'The next time we come here, I’m buying something from them,' says Sarah. Most of these women are from rural areas who've come to Hanoi seeking work. Perhaps they earn $20US a month to send back to their families. Most are married to farmers, but they don’t earn enough to support a family. Others are the sole bread winner. They work incredibly long hours, sleeping in cheap hostels, and seeing their families only briefly every few weeks or months. We return to the hotel for a quick costume change, before heading out again to our final meeting at the offices of SCDI. The Center for Supporting Community Development Initiatives has a broad remit, working with sex workers, MSM (men who have sex with men), people with HIV, children, and drug users. We’re here because, once again, an Australian friend, Justin Koonin, has introduced us to the organisation. According to its website, SCDI ‘deeply believes that each individual and community has great hidden potential, which can be used not only to tackle their own problems, but also to contribute to the development of the society. Through the approach of empowerment together with policy advocacy, SCDI aims to create motivation and an environment for these potentials to be realized in favor of positive goals.’ SCDI is a little different to the other organisations we’ve visited. It’s the first place we’ve seen clients in the building, sitting on the porch and watching the river that flows opposite. We’re meeting with Ms Nguên Thi Kim Dung, who brings us coffee mugs of cold water and seats us on couches in a new meeting room. We tell her about the meetings we’ve already had, and the ideas that different organisations have suggested for a large-scale, formal, fundraising concert. Kim pauses before responding. These are all organisations she knows, so she understands the issues around the upcoming withdrawal of funding to them. However, she's concerned that a formal concert at the Vietnam National Academy of Music will alienate SCDI's core constituents, who Kim describes to us as low-class. She acknowledges that while music should be for everyone, these MSM and transwomen may well feel that a concert in a high status venue is not for them, something too elite to feel genuinely open to them. We ask Kim for suggestions. A free outdoor concert, perhaps at the Lake. It’s a public space, and for everyone. The Hanoi community is always there walking, or playing badminton, and on the weekend there’s the Night Market. The European community has spent the last month showcasing their various cultures at free outdoor events. The embassies hired the space, brought in a stage. Mel thinks that perhaps one of the embassies can partner with us. Once again we are grateful that we came to Hanoi. We want to include as many parts of Hanoi’s LGBTQI+ community as possible, and while all these NGOs work broadly across queer issues, their specific demographics and areas of focus differ significantly. Internally, we tally up the mistakes we could have made, the people we could have inadvertently excluded, if we’d just landed with the choir and done one show. We thank Kim for seeing us. Before we leave, Sarah ducks into the bathroom. It’s the first place either of us has seen a sharps bin in Hanoi, a reminder both of who SCDI is supporting, and its commitment to providing proper care for people with issues largely invisible to us tourists in Hanoi. Kim’s right - music should be for everyone. We add to our list of tasks how we can help people who feel excluded from much of society believe that Pacific Pride Choir is singing for them too.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Mel & Sarah

Currently blogging from home, in iso like everyone else, and catching up with PPC19 in the form of a daily photojournal. Archives

June 2020

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed