Tales of Pacific Pride

Wat Damnak, site of Cambodian Living Arts' Heritage Hub Wat Damnak, site of Cambodian Living Arts' Heritage Hub Tuesday is a day for double-dating. Apart from our two dates with the LGBTQI community, we also have two dates with arts groups in Siem Reap, at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of size and reach. The first is with Kai from Cambodian Living Arts, who Mel met at the Bambu Stage on Sunday night. He’s invited us to the Heritage Hub at Wat Bo, an old Buddhist monastery and pagoda in the middle of town. We start by watching an Ethno-Cambodia workshop - for one week, 30 young musicians from around the world, all playing traditional instruments, have come together to teach each other their music. By mid-afternoon they’ve already learned three songs (apparently the Swiss piece was a bit of a challenge for some of the more microtonal instruments), and it’s currently the turn of the Indian team to teach. There’s an amazing array of instruments in the room; some we recognise: drums, guitar, violin, traditional Cambodian instruments and a Japanese sho. There are also five singers. The Indian flautist plays his piece phrase by phrase, each musician learning by ear, some copying tentatively, others with evident gusto. Some annotate small notebooks. The singers have moved to the stage area to learn their part. If they were after quiet, they won’t find it here. You need to be a quick learner in this environment as each teacher only has about 30 minutes. Looking at the different instruments, we wonder how this piece will ever come together, particularly as the tempo dramatically increases. One player, on what appears to be a single-stringed instrument, looks pleadingly at the teacher: 'It's hard to go faster on this instrument, perhaps a little break between verses would help?' But by the time Kai returns for us, the Indian piece is rocking along. Sarah in particular is blown away by the concept. Kai has much more to share with us, though, including the story of Cambodian Livings Arts, whose founder survived the Khmer Rouge by being quick to pick up the national songs they gave him to play. After the regime’s end, he found Cambodian traditional music had disappeared - those musicians who had managed to survive couldn’t make money from their art and had abandoned it. So began CLA’s long quest to rebuild Khmer art and create a living for artists. The female drumming group Medha is just one of their ensembles, and they’re also currently helping the Khmer Magic Music Bus, which travels to rural areas to demonstrate and teach traditional music to kids. (A bit like our Musica Viva program but with a cooler name.) Kai has plenty of suggestions about places we could perform, including at the Heritage Hub, and artists who might perform with us. Personally we love the idea of putting a Rainbow Choir on a Magic Music Bus - it sounds like Enid Blyton meets The Wiggles - but we’re not sure we’re quite the target market! We are definitely at home with our next music appointment however - 6.30pm is time for choir! Yep, you heard right, we’ve actually found a choir in Siem Reap. They’re called the Siem Weep Singers, and they’re run by Deborah Saunders, another Aussie ex-pat who upped stumps and moved here over ten years ago. The choir is currently a small group of expats who get together on a somewhat ad hoc basis to sing easily teachable world music and popular songs. They’re always keen to welcome new voices and tonight, we’re bringing three. In a sign of what a small world it is, Sarah’s friend Diana is also in Siem Reap, supervising nursing students. Sarah and Diana met and bonded over Old and Middle English in the mid-2000s when both writing their PhDs, and have run into each other randomly at Sydney Philharmonia rehearsals where Diana sings and Sarah’s on the roster as an emergency conductor. We’d all planned to have dinner, but Diana is up for a sing before supper, so she joins us there. The Siem Weep Singers (glad to know a good choir pun is an international phenomenon) is a small group of women. The nature of contract work here means that people come for two years then leave. Again it’s a familiar theme. Adam told us earlier that you have to work at staying connected in Siem Reap. People come for two days, two weeks, two months or two years, but after that, they usually move on. We’re welcomed warmly. What a refreshing change from Sydney where it is can be so hard to break into a new group and feel instant rapport. With three extra singers tonight we just about double the size of the group. We sit at a small kids’ table with an array of instruments including a ukulele, bells, and maracas. The group rehearses at the Small Art School, a self-financed art school providing free art education to Cambodian children. The associated gallery sells the kids' artwork and the money raised is split three ways between the artist, gallery operating costs and funding for the education program and art materials. Through this work, not only is the gallery the providing kids with an opportunity to make a living from their art, it’s also providing them with much needed business skills. The plastic choir folders are bursting with songs and lyrics. Over the years those who have joined have left songs to add to the collection. Deborah plays the ukulele and sings all the parts for us to copy. We have quite a few songs in common; maybe the Siem Weep Singers can join us for an item in July? We have great fun, and puppy cuddles from wrinkly little Tulsi, choir member Nicole’s seventh adoptee (she volunteers at one of only three vet clinics in town). Sarah’s invited to leave a song with the group and teaches Freedom Train. After dinner together at the local Thai, Deborah drives us home in her red-and-white polka-dotted tuk-tuk, christened ‘The MAD-Dame Mobile’. Anyone looking for a song in their heart and a spring in their step in Siem Reap should look her up.

0 Comments

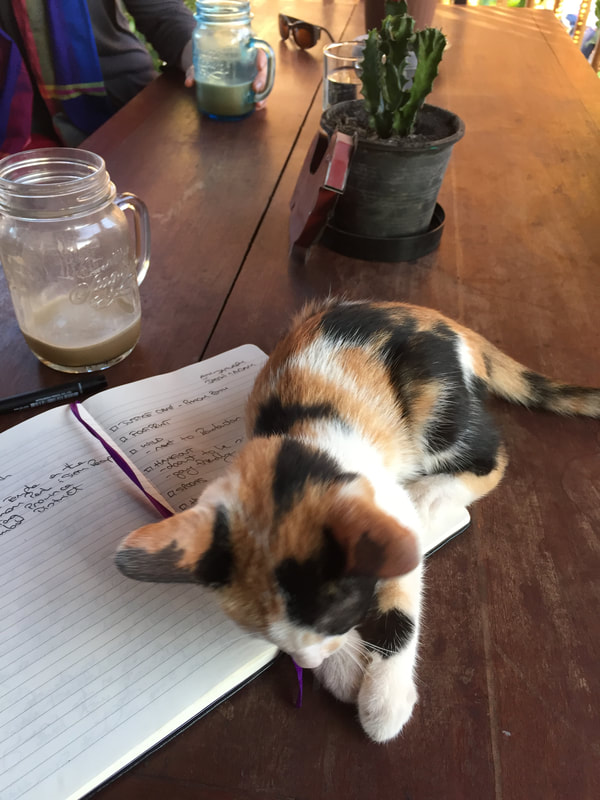

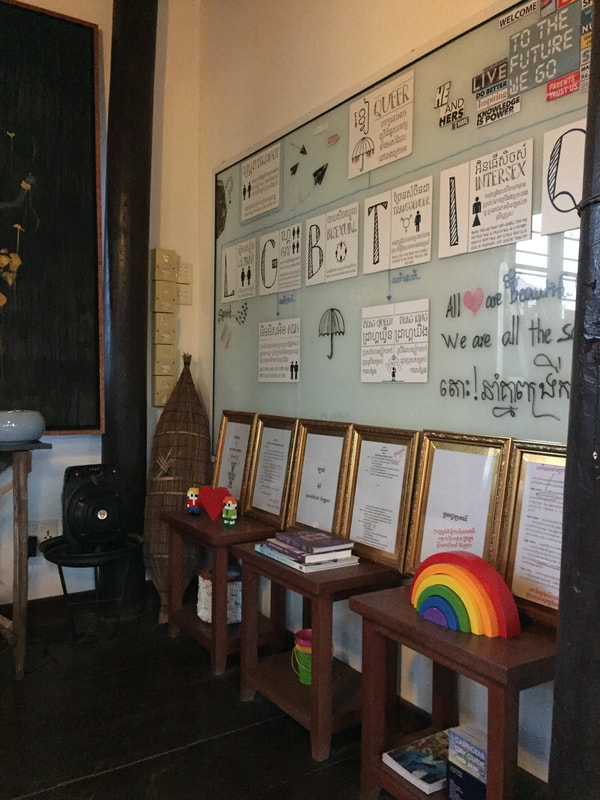

Jason & Freddie at A Place To Be Yourself Jason & Freddie at A Place To Be Yourself 10am Tuesday, and we're sitting in an Australian-owned, Cambodian-run cafe, The Little Red Fox Espresso, reportedly the best coffee in Siem Reap. We’re meeting Jason Argenta, founder of A Place to Be Yourself, a drop-in centre and safe space for LGBTIQ+ people. Originally from Perth, Jason came to Siem Reap about five years ago, volunteering to build houses and to teach. He loved working in the villages building houses, and quickly discovered that teaching wasn’t his thing. One month after his holiday to Cambodia and then Europe wrapped up, Jason had sold up everything he owned in Australia, to move to Siem Reap on New Year's Day. This is a theme we’ll hear repeated again and again by the surprising number of Aussie expats we meet - come for three days, never leave (PPCers, you’ve been warned!). With qualifications in Psychology and Sociology and working in Child Protection, Jason had volunteered at an LGBTQI drop-in centre in Australia. But as we’re discovering, there is something about Cambodia and Siem Reap in particular which draws you back. After selling everything, he moved to Siem Reap, and seeing a similar need, founded A Place to Be Yourself (APTBY). Surviving on fundraising and the odd contra arrangement, APTBY is open three hours every afternoon and employees two local Khmer staff: Pov, a trans man and Kunthea, a former street kid. Their office is on the first floor of the Purple Mango Wellness Centre, a typical Khmer stilt house, and offers a range of services including sexual health information, free condoms, and free counselling. On the covered deck, next to a spreading mango tree, lolls Freddie the genderqueer cat and his new kitten sidekick, Fanny. Despite the multitude of resources on the walls, the place feels instantly like home. An 'identity wall' spells out LGBTQI with Khmer explanations beneath. Both Jason and Pov explain that this is the best way to introduce these terms and concepts. People accessing the space can read the wall in their own time and then ask questions. In fact, this is how Pov came out as a trans man. He identified as Lesbian, but after having the identity wall explained to him, and the term Transgender highlighted, Pov walked away a new man. Not only did his life make sense, he knew he wasn’t alone. Pov came out to his family and it was difficult for his parents in particular to accept his choice. But after three years, his father finally said, 'You are my son.' Khmer people are traditionally gently-spoken and reserved, but there’s still raw emotion in Pov’s face and voice describing this seminal moment. Our day segued from the Little Red Fox to A Place To Be Yourself in much the same way as this blog post - what started as the best coffee in town with Jason, made by Adam’s expert LGT cafe staff at the Fox, has morphed into coconut coffee made by Jason at APTBY while Adam snidely offers barista training if he needs it. There’s a clatter from the kitchen in response as Adam, a Brisbane bloke who also threw in his Aussie life for Siem Reap, regards us cheekily over his bushy hipster beard. Both Jason and Adam are part of the network of LGBTQ business owners who organise Pride and other events in the town. We’ve hit the motherload of queer intel and by the time the sun is setting, and Freddie and Fanny reduced to rapturously purring puddles in our laps (make up your own jokes, we certainly did), we feel like we know every business and business owner, and how they fit into the rainbow jigsaw puzzle, even if we won’t manage actually to visit every establishment. Suffice to say, despite the massive boom in every kind of shop and eatery you can think of, you could stay here a good while and only support the pink economy if you so wished. It’s heartening to see how many of these businesses employ, partner with, or are run by, Khmer. Pov takes a photo of us standing under APTBY’s emblematic rainbow umbrella, each of your two pet-sick authors cradling a very compliant cat. It’s still amazing to us how easy it is to feel like old friends on first acquaintance with fellow queers, and how living a common experience of exclusion (despite obvious differences in degree) can break down language barriers to create an inclusivity that defies international borders. A Place To Be Yourself - isn’t that something we all could do with? On our third visit to Siem Reap, this more relaxed major city feels pretty familiar, but at the same time, as in Phnom Penh, the pace of change has clearly been fast. New malls and shops have opened, and there are a lot more pockets of upmarket and at times glamorous shops and eateries. Cambodia’s artistic and cultural capital is clearly on trend - even iced coffees served in jars at cafes with paleo menus have sprung up and are thriving.

Siem Reap is the final destination for the tour later this year, so we’re checking out the hotel and again, meeting with local LGBTQ groups and arts organisations with whom we can partner. We travelled overland from Phnom Penh by car instead of flying. It’s s great way to reacquaint ourselves with the land. The outskirts of Phnom Penh have seen a boom in the housing market. Many acres of land (once rice fields, we assume) have been turned over to identical series of grand, white residential apartments. We wonder who the target market is. Soon after, the familiar rice fields appear, the lush green stems swaying gently in the breeze. It’s Sunday, so no school today. Seems that it may be the only day of rest here for many, although the villages buzz with life and every shop is open. It’s a good day for weddings, and we pass over a dozen; you hear them before you see them, traditional music blaring from tinny speakers. Coloured marquees are set on the edge of the dusty road, chairs with elegant covers arranged within. Women in shining traditional dress arrive on moto, wrapped in casual shirts to preserve their sparkling attire. We stop briefly at the Spider Market. Yes, they sell spiders - great platters of fried ones, big black hairy critters pulled by hand from burrows in the hills. But if spider isn’t your thing, not to worry -there’s deep fried cricket with fresh chilli. The rice fields now are dotted with palm trees; a further sign that we are heading north. The roadside street stalls have changed too: stall after stall of sticky rice. These stalls, more than anything, remind Mel of Siem Reap. The rice is packed into tubes of bamboo (which serves not only as a cooking vessel, but also a compostable takeaway container) and cooked over charcoal. To eat, simply peel the bamboo away. It’s a delicious snack. Just before 2pm we arrive at the Angkor Paradise; our palatial hotel has a light, open foyer, polished granite floor and solid Khmer timber furniture. The staff are immaculately and formally dressed, but welcoming. We feel very underdressed and slightly grubby after our overland trip from Phnom Penh. We’ve been upgraded to a room on the Paradise (5th) floor. There’s plate of fruit and welcoming note from the General Manager. Note to self: dress more appropriately next time... Tonight we’ve been invited to the soft launch of a new show, 'The Call', by drumming group Medha, a new show produced in conjunction with Cambodia Living Arts. This all female drum troupe is seeking to break gender stereotypes in a country where drumming is seen as a male pursuit. Our names are on the door list and Mel is met by Nick Coffill. Hearing my accent, he says, 'You’re not from Sydney, are you? We don’t let people from Sydney in.' It’s clear by his accent and the cheeky glint in his eye that he too is Australian, from Condoblin, in fact. He suggests that Mel pretends to be from Canberra for the night. Nick's been in Siem Reap for six years as Creative Director of the Bambu Stage, a performing arts platform providing a space for artists and puppeteers. He’s interested in our project, suggesting that choirs are needed here. The arts scene in Cambodia was one of the many things destroyed during the Khmer Rouge, and Bambu Stage is one of the many arenas through which artists both Khmer and international are attempting to rebuild it. Bambu Stage is especially interested in Khmer art; of the three stages, one presents a puppet show, with puppets made onsite. There’s no program to go with the night’s performance, but you don’t need to understand Khmer to understand the unfolding story, told though drumming, singing and traditional Cambodian instruments including the korng vong thom and roneat (resembling gamelan instruments). The six women contrast traditional drumming with explorations of modernity: individuality, social isolation and claiming a space for female artists in non-traditional roles. The impression that women playing these particular traditional instruments is transgressive is clear from the moment they take the stage, as is their joy in performing. It’s a refreshing blend of theatre and music, contemporary and traditional, that wouldn’t be out of place at one of the globe’s better fringe festivals. And it’s right here in Siem Reap - after such a successful evening, we hope to see many more shows from Medha. Everywhere we go the message is consistent: things are relaxing here and the economy is moving. With more money flowing in to the country, there are more opportunities for people. Skyscrapers are appearing on the horizon; shiny investment bank buildings and hotels are springing up. But poverty is still a huge issue, as our meeting with Srorn showed us.

There seem to be two types of businesses here too. Those like Blue Chilli which carve out a space and thrive, and those that look like fantastic start-ups and sputter into life only to close their doors after a couple of years. Today is a hit-and-miss day full of just this kind of contradiction. We're looking for alternate venues for our performances in Phnom Penh and have a list of gallery spaces to view. We’ve got the list sorted and hope that our patient driver, Mr Viriya, finds us more organised today. META House looks promising. Opened in association with the International Academy at the Free University of Berlin, it boasts three floors of gallery space and a media lounge. The open upstairs area would seat around 50. The downstairs gallery is small and currently hosting an exhibition centred around environmental awareness. This seems to be the biggest change in the ten years since we’ve been here: a growing awareness of our impact on the planet. Our hotels offer free water re-fill stations (important in a country where the tap water isn't drinkable) and there’s a move away from plastic straws. Some shops use paper bags made from old newspapers with string for handles. No middle-aged white people here, demanding their right to a plastic bag. Surely it can’t be that hard... As part of her Make Art Not Waste project, Nina Clayton’s 'Ocean Cry' echoes the thoughts of many of us. It’s made from plastic refuse collected from the beach. Another work is a perspex box (60x30x40) full of items the artist has consumed in a five-month period: medication boxes, foil blister packs, cigarette boxes. It makes you stop and think. Despite providing food for thought, META House isn’t going to fit us, and the next two galleries are permanently closed, although their websites look up-to-date. (Pro tip - always double check on Facebook., ubiquitous in this part of the world). Mr Viriya is patient, but we sometimes wonder what he makes of all this. The cool and spacious French Institute of Cambodia looks more promising. There’s a gallery with several rooms of a beautiful exhibition by Caroline Chevalier and students, and an outdoor courtyard. It’s also close to the bridge over the Mekong so would be handy for Sanh and the trans community, provided the venue is one they’d be comfortable in. A certain level of informality is the best way to engage the biggest cross-section of LGBT in this part of the world. The administrative offices across the road have a huge sculpture of a bull on the sidewalk made almost entirely of bicycle chains. But it’s this evening, our last night in Phnom Penh, that we’ve really been looking forward to. We’re off to Counterspace Theatre at Java Creative Cafe (one of three in Phnom Penh), thrilled that Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA have a show on the weekend we’re in town. Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA is Cambodia's first gay dance company. We’ve been following them since they popped into our inbox in one of Rambutan’s newsletters, 3 years ago. The fledgling company's website describes it as re-staging: ‘Khmer classical dance with a vital freshness to create original, groundbreaking works at the intersection of art and human dignity. The dancers seek to infuse their tradition with a contemporary spirit, elevating the quality of life and expression for LGBTQ people in Cambodia and beyond.' Prumsodun himself, the choreographer and creative behind the company, is a child of Khmer refugees, born and raised in the United States. Classically trained, he wanted to become an Apsara dancer ever since he first saw this female art-form on a family home video at the age of four. He describes how his Khmer colleagues tried to persuade him to return to Cambodia. Initially he refused, thinking he couldn’t bear living in a country and among a people he loved but not be able to do anything to salve the poverty and hardship. Apsara dance is over 1,000 years old, and, with over 1,500 hand gestures alone, young girls commence training as early as five years old. It’s a complex art, requiring great flexibility of the hands and feet, which makes what we have seen tonight all the more powerful. Of the six dancers on stage, five of them commenced their training in Prum's lounge room only three years ago; the remaining cast member is Prum himself, who started his training in late high school when his sister’s Khmer dance teacher agreed to train him. The hour-long program features four classical dances, an excerpt of Prum’s own show BELOVED, and a contemporary dance duo to Sam Smith's 'Lay Me Down’. The three apsaras who first appear on stage are familiar to anyone who has seen Khmer classical dance - except their chests are bare. This is the only trait revealing their maleness; otherwise, they are as exquisitely dressed, made-up and delicate in movement as their female counterparts. The performance explores both gender fluidity and homoeroticism, with the soundscapes to the excerpts from BELOVED including sensuous poetry along with a dance narrative full of longing and desire. The contemporary duet between two young men manages to be both beautifully executed and vulnerable and raw; the nerves of young love, overlaid with possible fear of rejection (by the beloved? by family? by society?), tremble in every movement. At the end of the show, Prum tells us that classical art is about representing heaven, where all things are perfect and beautiful. He asks what it says about a society when its vision of heaven has no place for you - if there are no gay men represented in heaven, what can it mean except you have no place there: you are nothing; you are dirt; you are unworthy? Prumsodun & his troupe's work in carving a place for gay men in the heaven of Khmer classical dance is claiming an equal space for gay men in Cambodia; another testament to the power of art to create change. If you’re in Phnom Penh, see this show. It’s not often we wake up the same day that we go to bed ... we're old lesbian nanas who don’t go clubbing and so in the words of the late Aunty Mark, we should 'hand back our gay cards'. But not tonight. Tonight we’re ‘taking one for the team’ and going to a drag show.

Since we first came to Cambodia 10 years ago, the one constant in the gay scene has been the Blue Chilli. Established by Sokha Khem in 2006, it’s now an institution. Sokha was born in Svay Rieng province, and grew up as a farmer. His family and village were poor and he didn’t feel that he had a future there. He moved to Phnom Penh and did all manner of jobs: moto driver, cement worker, charcoal maker, even working for an NGO. With a bit of luck, and support from friends, he established Blue Chilli. 12 years on and the bar and the LGBT scene here has changed. We’re welcomed warmly by the staff. The music is pumping and we sit outside where it’s comfortably loud. It’s at least an hour until the hour-long drag show, although we do wonder if the rumours are true and we might be running on gay time tonight. It’s mostly gay men, but we don’t feel uncomfortable or out of place. Sokha is talking with patrons and finds his way over to us. He starts to tell us about the establishment of the bar and how the LGBT scene was very different then. 'Now', he says, 'it’s more open'. He too laments the demise of the lesbian bars in Phnom Penh and confirms our theory that lesbians aren’t really big on the nightclub scene. There are three drag shows a week by young artists. Sokha’s working with a new designer and the new costumes should be finished in about two weeks. He’s expanding the shows to five nights a week. He's philosophical about how it will all pan out, particularly mid-week when people do need to work the next day. More people arrive, including some straight couples, who wander inside, turn around, and wander out again. 'Not the target market,' quips Sarah. Others stay; this is clearly a place where everyone is welcome, provided you’re comfortable running the gauntlet of beaming young men waving chilli-shaped menus (it’s not such a hardship, even two middle-aged lesbians like us find them adorable). Surprisingly close to the advertised start time of 11pm, the music inside changes and everyone starts to press in towards the small stage. Showtime! For an hour, we are captivated by a series of young artists. The girls (and their two hardworking male sidekicks) can really dance. There are no grotesque parodies of womanhood in the dance routines, just a lot of joy, heart and skill (props to the queen who danced across the bar in towering red patent leather stilettos and vaulted back to the stage from the bar top at the end of her routine). It’s refreshing to be in a gay bar where everyone feels so comfortable, you don’t stick to the floor, and there’s no queeny cattiness to stick to you. Only one age-related gag at the expense of the queen who turns out to be having a birthday, but all is forgiven when a tiny cake is handed up to the stage and she starts to cry, jeopardising her magnificent eyelashes. We’re almost too engrossed to notice the bar is absolutely packed and heaving by the show’s conclusion. Blue Chilli’s clearly not going anywhere, but, as the routines end and the first ABBA of the night starts up, we sure as hell are. Tuk tuk! Dirk has told us that it’s winter in Cambodia ... hmmm, perhaps not today.

Ever the optimists, we dressed early this morning in our best 'tidy blue', today's colour according to traditional Khmer dress. After a bowl of tasty soup for lunch at the Russian Market we are dripping with sweat and less than tidy. We’ve got an hour and half until our meeting with the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights (CCHR). We call our driver and head back to the hotel. A quick swim, back into the tidy blue, and off we go. CCHR is a non-aligned, independent, non-governmental organization that works to promote and protect democracy and respect for human rights throughout Cambodia, including Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression rights. We fill CCHR representatives in on our project and who we’ve met. The discussion is wide-ranging. Interestingly, LGBTIQ people in Cambodia face numerous forms of discrimination, partly because of a legal framework which denies them basic equality. In particular, LGBTIQ people in Cambodia face four main forms of legal discrimination, including the lack of legal protection against discrimination and violence against LGBTIQ people; the absence of legal recognition of self-defined gender identity; the absence of marriage equality in Cambodian law; and the denial of full adoption rights to rainbow couples. CCHR representatives confirm what we knew from our previous trips here and what Srorn has reinforced with us. Family is everything, as is community. Many young LGBTIQ people have felt that they needed to leave their homes because of their gender identity. For this reason, CCHR representatives tell us, Cambodian LGBTIQ people identify marriage equality as their most pressing desire. The institution of marriage is exceptionally highly-valued in Cambodia, and excluding LGBTIQ people from the institution of marriage excludes them from one of the foundations of Cambodian society. Our telling of Pacific Pride Choir’s foundation story and the history of LGBT choruses around the world is growing more concise. Our mission this time is different to 2017, and yet strangely similar. Different, purely because choirs just aren’t a thing here. Similar, because most people have some kind of family and most of us in the LGBTQI community have experienced discrimination, whether from family, religious institutions, schools or places of work. These are universal themes. In our singing we hope to create a space for others to join and share their stories, to know that they are not alone. CCHR representatives listen and seem comfortable with our ideas, glad that we’re consulting with different local groups and that we want to collaborate. They help to put us in touch with other players, and mention the recent event 'Our Lives, Our Rights' organized by Rainbow Community Kampuchea (RoCK) to celebrate their 10 year anniversary and the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at The Mansion (Foreign Correspondents' Club), a venue we’ve arranged to see later that day on Srorn’s suggestion. While we’re grateful to live where we do, it’s clear that we Australians have a lot to learn from LGBT activism in South-east Asia. It’s 7.30am and we’re at breakfast already, ready for the day. Those of you who know us know that there is no way that we are ever out the door at this time of the day, despite getting up early. But here we are.

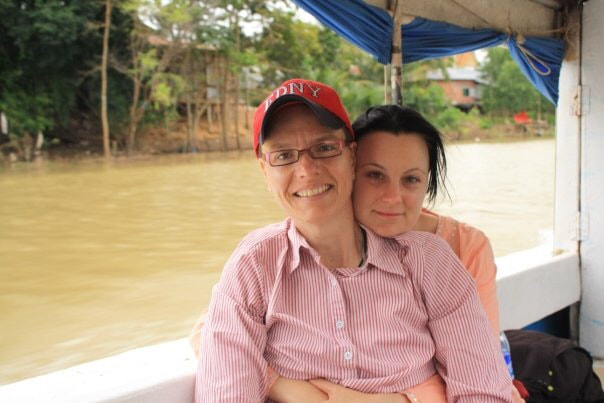

Since yesterday Sarah has been messaging Srorn about a purchase for the members of Pacific Pride Choir. There’s a Facebook Page, Rainbow Cat (Rainbow Cambodia Advocate Team), founded to support the human rights of everyone, not just LGBT as it is known here. They support social enterprise and provide funding to help the poor and the disadvantaged start small businesses. As little as $100 USD can fund a street seller. Srorn tells about Pheng Sahn, a trans man who lives across the Mekong River. Seems there is quite a trans community here. Sahn is a weaver and weaves rainbow kromer, the traditional Khmer scarves, to support his family. We see photos of the stunning fabric. Sahn and his female partner have been together since 1979, says Srorn; before Sarah was born (‘only by a year,’ says Mel). We’d planned to buy a couple of traditional kromer for ourselves and had been going to look for them in Siem Reap. We know a guy who knows a guy who sells them and another who will hem them. Quick change of plan. We do the maths and run the logistics (getting the kromer, getting them back to Sydney and then over to Hanoi), as both Srorn and Sahn are heading off on Friday to tour to Prey Veng, where Sahn will speak to the village community about his life as a trans man as part of the My Voice, My Story exhibition. We order 35, enough for each member of the 2019 tour and a few extra. Facebook Messenger is a wonderful tool (can’t believe we said that). We place the order and Sahn will arrive Friday at 9am with the scarves. Activists like Srorn and Sahn don’t have salaries for their work. Our purchase will fund their families and their advocacy. The softly-spoken Mr Bee and his colleagues at Rambutan help us translate for Sahn when he arrives on his moto. He recognises Rambutan as the site of last year’s Pride Pool Party. Mr Bee is nominated by his co-workers as ‘the photographer’, and so he artfully arranges our kromer and snaps away, posing our hands in the symbol for ‘love’. He shows us another way to wear kromer on his phone: in a photo an exceptionally buff young man reclines on his side, framed by blue sky, wearing nothing but a vibrant rainbow kromer wrapped sarong-style around his groin. ‘This is me,’ shy Mr Bee has to point out to us. As we leave for the day in Mr Viriya’s gold Lexus, complete with wicker heart dangling from the mirror, Sahn and the Rambutan’s gruff butch security guard are hanging out together out front, clearly old friends. We’ve learned something new about two of the Rambutan’s staff this morning, all thanks to rainbow powerhouse Sahn. We first came to Phnom Penh 10 years ago. It was our honeymoon, and Cambodia’s capital was the first stop on our 12-day Intrepid tour. November was hot, humid, & bustling. Jet-lagged, we headed straight out of our hotel with a few hours to kill before the welcome dinner. We soon discovered clear footpaths were a luxury not afforded most streets. If they did exist, they were turned over to sidewalk restaurants, mechanics workshops or moto parking lots.

We were an oddity, walking the length of the main street, waving away the constant refrain of, 'Hello, you want tuk tuk?' But we were instantly captivated by the steaming, chaotic city and its surprisingly relaxed inhabitants. There wasn’t much development then; a few shiny banks & less than a handful of high-end hotels. Fast forward to 2019 & the change is evident. As with Hanoi, the juxtaposition of old & new is stark. But now, the city that seemed frantic to us ten years ago feels different. The pace of life remains far less frenetic than Hanoi. This city, though busy, is more chilled. We meet with Dirk de Graaff, who owns the Rambutan with his partner Tum Hantitipart. We’re hoping to gain a Westerner’s tips on the gay scene here & to avoid any rookie mistakes, like the one we made ten years ago. (More on that later.) There's a divide between the city LBGTQI and the rural; the two rarely intersect. Dirk stresses that it's not a community in the sense that we know. We ask about gay bars, having noticed that Blue Chilli has been around since 2006. Most of the others sputter into life and close within two years, he tells us. Finding a lesbian bar is hard. We ask about The L Bar, opened in 2016 by two French women - closed. 'All I know about the lesbian scene is that they head off on motorbikes & go somewhere', says Dirk. ‘I saw a documentary about it once. I don’t know how it works.’ Sarah has a sheepish smile on her face; it’s time to fess up about our one and only attempt to find a lesbian bar in Cambodia, on our last night in Phnom Penh, all those years ago. At the mere mention of the Pussycat Bar, Dirk collapses in laughter. Seems we don’t have to explain all that much. Our tour guide of 2009 helpfully suggested a bar to us that he thought lesbians could go to. Pussycat Bar - it sounded cute. Somehow we managed to pick up a tuk tuk driver from our hotel who was clearly a screaming queen. ‘Pussycat Bar!’, he trilled, as we tucked ourselves in behind him. We’d dressed down for the evening, in our standard tourist guise of knee-length shorts and long-sleeved shirts. We’d made the mistake previously of dressing up to go to a gay bar in Siem Reap and found everyone was in t-shirts and jeans, so we figured the Cambodian scene was more relaxed. Our tuk tuk pulls up outside a narrow entranceway, lit with neon, the pavement in front crowded with moto and with some big guys dressed in leather. We head down the stairs to find more neon lighting a narrow bar, a large pool table, and about a dozen girls. They’re all young, they’re all gorgeous, with long, flowing hair, they’re all immaculately made-up, and they’re all wearing very short skirts. We like to think we don’t stereotype, but we’re pretty surprised at how different Khmer lesbians look to those we’ve met around the rest of the world. We sit at the bar, feeling seriously under-dressed, and look over the menu, trying to make bright conversation with the bartender. They don’t have most of the drinks listed on the menu. As we peruse it, we find a semicircle of girls closing in on us. One in particular seats herself next to Mel and starts asking questions - ‘Where are you from?’ We feel like somehow this cultural exchange isn’t panning out quite as we’d expect. The girls are looking at us expectantly. They seem to be much more interested in Mel than in Sarah, but it’s clear the ringleted lass doing most of the talking has adopted her, and the other girls slowly drop away as her pout deepens. They try and entice us off the bar stools, to which we are firmly rooted, to play pool. Mel, quite keen on pool from her days as a university chorister, isn't going anywhere, despite encouragement (from Sarah included, who knows her wife likes pool). Mel later confesses she wasn’t bending over a pool table for anybody. By this point we both think there’s definitely something going on we can’t fathom, finish our drinks and pay up. We thank the girls and depart. As we leave, the burly guys in black leather hustle for our business: ‘Moto?’ ‘Tuk tuk!’ shrieks our driver, waving his hands in the air and leading us across the road to his vehicle at a trot. On the way home, he tries to convince us to go to a drag show at Blue Chilli, but we’re done for the night. Back in our hotel room, Mel confesses she really needed the bathroom but was too scared to make a move. Sarah says the same, and we both shake our heads and laugh. It takes ten years for us to find out about ‘hostess bars’, and by that point, Dirk is laughing about as hard as we did. Oops. Where to begin?

It’s evening of our first full day in Cambodia. Our heads are exploding with information; our hearts are already full with some of the stories we’ve heard. We’re glad to be back in this crazy-beautiful city after nearly 10 years, and back in the gay-owned Rambutan Resort, in whose sister hotel in Siem Reap we first thought about bringing a pride choir to Cambodia. We had our first meeting with an LGBTQI organisation, Cam-ASEAN, this afternoon, in the Starbucks at Bokor traffic lights (yes, they’re a landmark). The Starbucks is large, cool and clearly a popular meeting place. We’re meeting with activist Srun Srorn, who tells us one of his current projects is providing job opportunities for young LGBT people to prevent them from homelessness. Employers can sign up to receive CVs from young folk at risk once they’re proven to be able to provide a safe working environment. We’re at Starbucks Bokor because the boss there has signed up. We’ve ordered our coffees (‘two coffees for Miss Sarah’ calls the young barista) when Srorn and his colleague Pheung Sophea arrive, straight from another meeting. We know that Cam-ASEAN is responsible for the brand new SOGI curriculum (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity) to be rolled out nationally for high school students as part of the Life Skills curriculum in 2019. We have lots of questions about it, particularly considering our own Australian government has just withdrawn Safe Schools, an equivalent program, from our own schools. But the story Srorn launches into about Cam-ASEAN’s current project is beyond incredible. Srorn tells us of his work to create the same recognition for lesbians and trans people at an official level as there is for gay Khmer. Several years ago, he faced the official position that there were hardly any lesbians or trans people in Cambodia; since then he has worked to help dispel that myth. Cam-ASEAN's recent work is to go into villages and connect with trans and lesbian couples. We ask how they identify these people, and are stunned by his response. Srorn and Sophea travelled from village to village, all over Cambodia. They asked the local police, the tuk tuk drivers, and the street sellers - people who know most of the village - 'Do you know any men who dress like women, or women who dress like men?’ ‘Yikes!’, Mel is thinking, 'Can you imagine that approach back home, where coming out is such a personal thing and we round on anybody who publicly 'outs' someone?’ Meanwhile, Sarah is impressed at the perseverance of such a painstaking approach to gathering information. It seems a direct approach works, and works well. For many couples, the old cliche of being ‘the only gay in the village’ was true. Yet in one village alone, 7 long-standing trans couples identified themselves and are part of the project. Many of these couples have been together for over 40 years and survived the Khmer Rouge regime (that, in itself, does our heads in). Outside their village community, all these couples have come to realise they are not alone. And likewise, so have their neighbours and families. Their stories are collected in a roving exhibition, ‘My Voice, My Story’. Just like Srorn and Sophea when collecting the stories, the exhibition now roams from village to village. Neighbours weep as they hear the stories of people who have been living among them all their lives. But the point of the project - of any of Srorn’s projects - isn’t to inspire pity for the difficulties of a queer life. It’s to empower LGBTQ people to show the strength in their lives. They have identified 5,000 people across Cambodia living in long-term (decades-long) trans and lesbian relationships. These elders were unknown to the young queer folk now centred on Cambodia’s big cities, or who have moved overseas. But now the faces of these elders are being seen, their stories are holding up the young folk, and, more importantly, they are stepping forward as key contributors to their own communities. Srorn shows us a video of a transman and his partner who are setting up a home for the old and poor in their community. It’s the same video we saw over breakfast this morning, reading up on Cam-ASEAN. This story was the tip of the iceberg in our 90-minute conversation. Srorn is a passionate activist. He’s not the type to stay with one organisation, resting on his laurels. He tell us that he founds groups and then, when they secure funding, he leaves to start something new in the next area he feels needs development. He and Cam-ASEAN also use a model in all their projects which trains people to speak for themselves; young LGBTQ folk on Facebook live are interviewed about their lives, and then become the interviewer for a queer friend in their circle in a subsequent episode. Similarly, trans men and women accompany the roving ‘My Voice, My Story’ exhibition to rural villages, give their stories in person, and in doing so, train up the trans people in that village to speak about themselves. Srorn has several ideas about how Pacific Pride Choir can support Khmer people. It will take time for us to figure out which one we can make work. Whatever it is, we reckon it’s going to be something that could teach the Australian government a thing or two about recognition. On our last night in Hanoi, we’re having an early dinner before heading to the airport, and reflecting on the past week, the people we’ve met, what we’ve learnt, and what comes next.

People and organisations the world over are big on curating ‘listicles’: your top products, your best skills, your strongest reasons for action or thought; the list goes on. In the quiet of the hotel restaurant, we compile our own top 5 list: a list of what we can achieve by bringing Pacific Pride Choir to Vietnam. 1) We can inspire the first LGBTQI+ choir in Vietnam. If we can bring 40 singers to Hanoi, iSEE has undertaken to found a Diversity Choir. This is one extra choir on the planet - and one extra LGBTQI+ choir, to boot - added to our diverse international choir family. We have a deal, or at least an in-principal agreement: if we bring singers to Hanoi, there will be singers there to welcome us. 2) We can help iSEE kickstart their new era of fundraising to assist with advocacy for LGBTQI+ people in Vietnam. Some of iSEE’s main funding sources are about to expire, meaning they need to build a profile around crowdfunding and philanthropy to keep doing the work they do. A formal concert, with an international choir, in an elite venue like the Vietnam National Academy of Music, will draw high profile celebrities, and the audience’s attention. 3) We can assist in raising the visibility of the LGBTQI+ community in the general community by giving free public performances in places with a lot of foot traffic. 4) We can provide a free concert for members of the LGBTQI+ community who won’t go to elite concert venues, who feel like such spaces, and the music in them, can’t possibly belong to them. These are some of the most marginalised people in the city. Maybe we can even provide an opportunity for some of them to perform, with a bit of mentoring first. 5) We can meet and make friends with a surprisingly large network of LGBTQI+ folk, who are passionate and articulate. Some people have expressed doubt that we’d find community to connect with in Vietnam. By now, shouldn’t we all have figured out that LGBTQI+ people are everywhere? For a few days next July, we can be a focal point for queer folk to unite, and, probably, party. There’s no doubt it would be easier if we toured to countries with established queer choirs, or if we joined in with long-running festivals. These choirs and festivals already have an existing network of supporters, and supportive venues. But what marked Sarah's time with Sydney Gay & Lesbian Choir was outreach. We sang for people and communities that didn't get much love: the children detained at Pontville in Hobart, detainees at Villawood in Sydney. It didn’t matter that we were LBGTQI+. We were a choir and we were willing to spare a few hours for anyone who wanted to listen. We remember at Pontville, we were told not many of the boys spoke much English, and most of them would have no idea what we were singing. But one boy broke into song during ‘Seasons of Love’. He knew every word. And he was Vietnamese. There are other kinds of outreach, too - the kind where you sing for churches, synagogues, nursing homes, hospitals, in public parks, at public events, anywhere where the general public will see you, and understand that LGBTQI+ people are, in some ways at least, ordinary human beings. This kind of work is the foundation of Pacific Pride Choir. It’s about putting the goals of the people you’re travelling to meet on par with your own desires as a tourist. There's a certain immunity that comes with being a traveler in a choir, too. At the end of our trip, we’ll get to head back to our own communities. What we want to do isn’t easy - as far as we can tell, there’s no choir quite like Pacific Pride on the planet - but when you’re looking people in the eye, and seeing them light up as you talk about the project, and what we may be able to do together, you remember what it's all for. We have huge support from our dear friends Oliver and Michael and all the staff at KIconcerts. We’re grateful that they make it so easy for us, and believe in what we’re trying to do. Everyone says travel changes you; that people travel so they can be changed. We prefer the kind of travel which offers a little change in return. So, the question is: what kind of a traveller are you? |

Mel & Sarah

Currently blogging from home, in iso like everyone else, and catching up with PPC19 in the form of a daily photojournal. Archives

June 2020

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed